Amun Ragahaha

Chelation is a type of bonding of ions and their molecules to metal ions. It involves the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central metal atom.[1][2] These ligands are called chelants, chelators, chelating agents, or sequestering agents. They are usually organic compounds, but this is not a necessity.

The word chelation is derived from Greek χηλή, chēlē, meaning "claw"; the ligands lie around the central atom like the claws of a crab. The term chelate was first applied in 1920 by Sir Gilbert T. Morgan and H. D. K. Drew, who stated: "The adjective chelate, derived from the great claw or chele (Greek) of the crab or other crustaceans, is suggested for the caliperlike groups which function as two associating units and fasten to the central atom so as to produce heterocyclic rings."[3]

Chelation is useful in applications such as providing nutritional supplements, in chelation therapy to remove toxic metals from the body, as contrast agents in MRI scanning, in manufacturing using homogeneous catalysts, in chemical water treatment to assist in the removal of metals, and in fertilizers.

Chelate effect

[edit]

The chelate effect is the greater affinity of chelating ligands for a metal ion than that of similar nonchelating (monodentate) ligands for the same metal.

The thermodynamic principles underpinning the chelate effect are illustrated by the contrasting affinities of copper(II) for ethylenediamine (en) vs. methylamine.

The thermodynamic approach to describing the chelate effect considers the equilibrium constant for the reaction: the larger the equilibrium constant, the higher the concentration of the complex.

| [Cu(en)] = β11[Cu][en] | (3) |

| [Cu(MeNH2)2] = β12[Cu][MeNH2]2 | (4) |

Electrical charges have been omitted for simplicity of notation. The square brackets indicate concentration, and the subscripts to the stability constants, β, indicate the stoichiometry of the complex. When the analytical concentration of methylamine is twice that of ethylenediamine and the concentration of copper is the same in both reactions, the concentration [Cu(en)] is much higher than the concentration [Cu(MeNH2)2] because β11 ≫ β12.

An equilibrium constant, K, is related to the standard Gibbs free energy, by

where R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in kelvins. is the standard enthalpy change of the reaction and is the standard entropy change.

A metal (from Ancient Greek μέταλλον (métallon) 'mine, quarry, metal') is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against nonmetallic materials which do not.[1]: Chpt 8 & 19 [2]: Chpt 7 & 8 Metals are typically ductile (can be drawn into wires) and malleable (they can be hammered into thin sheets).[3]

A metal may be a chemical element such as iron; an alloy such as stainless steel; or a molecular compound such as polymeric sulfur nitride.[4] The general science of metals is called metallurgy, a subtopic of materials science; aspects of the electronic and thermal properties are also within the scope of condensed matter physics and solid-state chemistry, it is a multidisciplinary topic. In colloquial use materials such as steel alloys are referred to as metals, while others such as polymers, wood or ceramics are nonmetallic materials.

A metal conducts electricity at a temperature of absolute zero,[5] which is a consequence of delocalized states at the Fermi energy.[1][2] Many elements and compounds become metallic under high pressures, for example, iodine gradually becomes a metal at a pressure of between 40 and 170 thousand times atmospheric pressure. Sodium becomes a nonmetal at pressure of just under two million times atmospheric pressure, and at even higher pressures it is expected to become a metal again.

When discussing the periodic table and some chemical properties the term metal is often used to denote those elements which in pure form and at standard conditions are metals in the sense of electrical conduction mentioned above. The related term metallic may also be used for types of dopant atoms or alloying elements.

In astronomy metal refers to all chemical elements in a star that are heavier than helium. In this sense the first four "metals" collecting in stellar cores through nucleosynthesis are carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and neon.

Force on a current-carrying wire

[edit]

When a wire carrying an electric current is placed in a magnetic field, each of the moving charges, which comprise the current, experiences the Lorentz force, and together they can create a macroscopic force on the wire (sometimes called the Laplace force). By combining the Lorentz force law above with the definition of electric current, the following equation results, in the case of a straight stationary wire in a homogeneous field:[31]where ℓ is a vector whose magnitude is the length of the wire, and whose direction is along the wire, aligned with the direction of the conventional current I.

If the wire is not straight, the force on it can be computed by applying this formula to each infinitesimal segment of wire , then adding up all these forces by integration. This results in the same formal expression, but ℓ should now be understood as the vector connecting the end points of the curved wire with direction from starting to end point of conventional current. Usually, there will also be a net torque.

Conventions

The conventional direction of current, also known as conventional current,[16][17] is arbitrarily defined as the direction in which positive charges flow. In a conductive material, the moving charged particles that constitute the electric current are called charge carriers. In metals, which make up the wires and other conductors in most electrical circuits, the positively charged atomic nuclei of the atoms are held in a fixed position, and the negatively charged electrons are the charge carriers, free to move about in the metal. In other materials, notably the semiconductors, the charge carriers can be positive or negative, depending on the dopant used. Positive and negative charge carriers may even be present at the same time, as happens in an electrolyte in an electrochemical cell.

A flow of positive charges gives the same electric current, and has the same effect in a circuit, as an equal flow of negative charges in the opposite direction. Since current can be the flow of either positive or negative charges, or both, a convention is needed for the direction of current that is independent of the type of charge carriers. Negatively charged carriers, such as the electrons (the charge carriers in metal wires and many other electronic circuit components), therefore flow in the opposite direction of conventional current flow in an electrical circuit.[16][17]

Reference direction

A current in a wire or circuit element can flow in either of two directions. When defining a variable to represent the current, the direction representing positive current must be specified, usually by an arrow on the circuit schematic diagram.[18][19]: 13 This is called the reference direction of the current . When analyzing electrical circuits, the actual direction of current through a specific circuit element is usually unknown until the analysis is completed. Consequently, the reference directions of currents are often assigned arbitrarily. When the circuit is solved, a negative value for the current implies the actual direction of current through that circuit element is opposite that of the chosen reference direction.[a]: 29

Early research in acoustics

[edit]

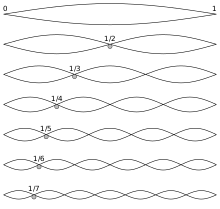

In the 6th century BC, the ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras wanted to know why some combinations of musical sounds seemed more beautiful than others, and he found answers in terms of numerical ratios representing the harmonic overtone series on a string. He is reputed to have observed that when the lengths of vibrating strings are expressible as ratios of integers (e.g. 2 to 3, 3 to 4), the tones produced will be harmonious, and the smaller the integers the more harmonious the sounds. For example, a string of a certain length would sound particularly harmonious with a string of twice the length (other factors being equal). In modern parlance, if a string sounds the note C when plucked, a string twice as long will sound a C an octave lower. In one system of musical tuning, the tones in between are then given by 16:9 for D, 8:5 for E, 3:2 for F, 4:3 for G, 6:5 for A, and 16:15 for B, in ascending order.[6]

Aristotle (384–322 BC) understood that sound consisted of compressions and rarefactions of air which "falls upon and strikes the air which is next to it...",[7][8] a very good expression of the nature of wave motion. On Things Heard, generally ascribed to Strato of Lampsacus, states that the pitch is related to the frequency of vibrations of the air and to the speed of sound.[9]

Comments

Post a Comment