Farenheit 451

Temperature Is thus the difference of differences

the difference between differences

the space between the lines

out of which the cease

less motion of change

rises against the

constant falling

of itself within

its sphere

of self

every down motion

has

an up component

action reaction

Where

expansion is not the opposite of contraction

the two forces are electricity and magnetism

magnetic force the proton of the circuit attracts

along the arc of all curves

Electrick Force the electron is attracted

moving in a straight line until

it hits a wall

bounces off

before returning

or

is absorbed

and returns to hydrogen

positive charge has palpable mass as half

the smallest unit of H

with no palpable motion

Negative charge has palpable motion

as the other half of H

with no palpable mass

emitting light 186,000,000 million miles/second

a base 60 number if eye ever saw one

as μ

rides the bus

at 0.00000012

leaving energy at the speed of sound

36/12

=3

Water rising is water breathing in

and expanding out

in all directions

from one point

Water falling is breathing out and contracting

in all directions to one point

if the center is the point the golden

ratio is followed to parse energy

if the center is not the point

the life decays

off center

the body decomposes

from turbulence

too much friction from too many

switches of direction too frequently

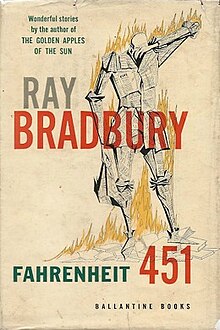

Fahrenheit 451

First edition cover (clothbound) | |

| Author | Ray Bradbury |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Joseph Mugnaini[1] |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian[2] |

| Published | October 19, 1953 (Ballantine Books)[3] |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 156 |

| ISBN | 978-0-7432-4722-1 (current cover edition) |

| OCLC | 53101079 |

| 813.54 22 | |

| LC Class | PS3503.R167 F3 2003 |

Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by American writer Ray Bradbury.[4] It presents a future American society where books have been outlawed and "firemen" burn any that are found.[5] The novel follows in the viewpoint of Guy Montag, a fireman who soon becomes disillusioned with his role of censoring literature and destroying knowledge, eventually quitting his job and committing himself to the preservation of literary and cultural writings.

Fahrenheit 451 was written by Bradbury during the Second Red Scare and the McCarthy era, inspired by the book burnings in Nazi Germany and by ideological repression in the Soviet Union.[6] Bradbury's claimed motivation for writing the novel has changed multiple times. In a 1956 radio interview, Bradbury said that he wrote the book because of his concerns about the threat of burning books in the United States.[7] In later years, he described the book as a commentary on how mass media reduces interest in reading literature.[8] In a 1994 interview, Bradbury cited political correctness as an allegory for the censorship in the book, calling it "the real enemy these days" and labeling it as "thought control and freedom of speech control."[9]

The writing and theme within Fahrenheit 451 was explored by Bradbury in some of his previous short stories. Between 1947 and 1948, Bradbury wrote "Bright Phoenix", a short story about a librarian who confronts a "Chief Censor", who burns books. An encounter Bradbury had in 1949 with the police inspired him to write the short story "The Pedestrian" in 1951. In "The Pedestrian", a man going for a nighttime walk in his neighborhood is harassed and detained by the police. In the society of "The Pedestrian", citizens are expected to watch television as a leisurely activity, a detail that would be included in Fahrenheit 451. Elements of both "Bright Phoenix" and "The Pedestrian" would be combined into The Fireman, a novella published in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1951. Bradbury was urged by Stanley Kauffmann, an editor at Ballantine Books, to make The Fireman into a full novel. Bradbury finished the manuscript for Fahrenheit 451 in 1953, and the novel was published later that year.

Upon its release, Fahrenheit 451 was a critical success, albeit with notable outliers. The novel's subject matter led to its censorship in apartheid South Africa and various schools in the United States. In 1954, Fahrenheit 451 won the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature and the Commonwealth Club of California Gold Medal.[10][11][12] It later won the Prometheus "Hall of Fame" Award in 1984[13] and a "Retro" Hugo Award in 2004.[14] Bradbury was honored with a Spoken Word Grammy nomination for his 1976 audiobook version.[15] The novel has also been adapted into films, stage plays, and video games. Film adaptations of the novel include a 1966 film directed by François Truffaut starring Oskar Werner as Guy Montag and a 2018 television film directed by Ramin Bahrani starring Michael B. Jordan as Montag, both of which received a mixed critical reception. Bradbury himself published a stage play version in 1979 and helped develop a 1984 interactive fiction video game of the same name, as well as a collection of his short stories titled A Pleasure to Burn.[16] Two BBC Radio dramatizations were also produced.

Phase diagram

A phase diagram in physical chemistry, engineering, mineralogy, and materials science is a type of chart used to show conditions (pressure, temperature, etc.) at which thermodynamically distinct phases (such as solid, liquid or gaseous states) occur and coexist at equilibrium.

Overview[edit]

Common components of a phase diagram are lines of equilibrium or phase boundaries, which refer to lines that mark conditions under which multiple phases can coexist at equilibrium. Phase transitions occur along lines of equilibrium. Metastable phases are not shown in phase diagrams as, despite their common occurrence, they are not equilibrium phases.

Triple points are points on phase diagrams where lines of equilibrium intersect. Triple points mark conditions at which three different phases can coexist. For example, the water phase diagram has a triple point corresponding to the single temperature and pressure at which solid, liquid, and gaseous water can coexist in a stable equilibrium (273.16 K and a partial vapor pressure of 611.657 Pa). The pressure on a pressure-temperature diagram (such as the water phase diagram shown) is the partial pressure of the substance in question.[1]

Enthalpy

| Enthalpy | |

|---|---|

Common symbols | H |

| SI unit | joules |

| In SI base units | kg⋅m2⋅s−2 |

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

In thermodynamics, enthalpy (/ˈɛnθəlpi/ ) is the sum of a thermodynamic system's internal energy and the product of its pressure and volume.[1] It is a state function used in many measurements in chemical, biological, and physical systems at a constant external pressure, which is conveniently provided by the large ambient atmosphere. The pressure–volume term expresses the work that was done against constant external pressure to establish the system's physical dimensions from to some final volume (as ), i.e. to make room for it by displacing its surroundings.[2][3] The pressure-volume term is very small for solids and liquids at common conditions, and fairly small for gases. Therefore, enthalpy is a stand-in for energy in chemical systems; bond, lattice, solvation, and other chemical "energies" are actually enthalpy differences. As a state function, enthalpy depends only on the final configuration of internal energy, pressure, and volume, not on the path taken to achieve it.

In the International System of Units (SI), the unit of measurement for enthalpy is the joule. Other historical conventional units still in use include the calorie and the British thermal unit (BTU).

The total enthalpy of a system cannot be measured directly because the internal energy contains components that are unknown, not easily accessible, or are not of interest for the thermodynamic problem at hand. In practice, a change in enthalpy is the preferred expression for measurements at constant pressure, because it simplifies the description of energy transfer. When transfer of matter into or out of the system is also prevented and no electrical or mechanical (stirring shaft or lift pumping) work is done, at constant pressure the enthalpy change equals the energy exchanged with the environment by heat.

In chemistry, the standard enthalpy of reaction is the enthalpy change when reactants in their standard states ( p = 1 bar ; usually T = 298 K ) change to products in their standard states.[4] This quantity is the standard heat of reaction at constant pressure and temperature, but it can be measured by calorimetric methods even if the temperature does vary during the measurement, provided that the initial and final pressure and temperature correspond to the standard state. The value does not depend on the path from initial to final state because enthalpy is a state function.

Enthalpies of chemical substances are usually listed for 1 bar (100 kPa) pressure as a standard state. Enthalpies and enthalpy changes for reactions vary as a function of temperature,[5] but tables generally list the standard heats of formation of substances at 25 °C (298 K). For endothermic (heat-absorbing) processes, the change ΔH is a positive value; for exothermic (heat-releasing) processes it is negative.

Vacuum permeability

| Value of μ0 |

|---|

| 1.25663706127(20)×10−6 N⋅A−2 |

The vacuum magnetic permeability (variously vacuum permeability, permeability of free space, permeability of vacuum, magnetic constant) is the magnetic permeability in a classical vacuum. It is a physical constant, conventionally written as μ0 (pronounced "mu nought" or "mu zero"). It quantifies the strength of the magnetic field induced by an electric current. Expressed in terms of SI base units, it has the unit kg⋅m⋅s−2·A−2. It can be also expressed in terms of SI derived units, N·A−2.

Since the redefinition of SI units in 2019 (when the values of e and h were fixed as defined quantities), μ0 is an experimentally determined constant, its value being proportional to the dimensionless fine-structure constant, which is known to a relative uncertainty of 1.6×10−10,[1][2][3][4] with no other dependencies with experimental uncertainty. Its value in SI units as recommended by CODATA is:

From 1948[6] to 2019, μ0 had a defined value (per the former definition of the SI ampere), equal to:[7]

The deviation of the recommended measured value from the former defined value is within

it uncertainty.

Vacuum permittivity

| Value of ε0 | Unit |

|---|---|

| 8.8541878188(14)×10−12 | F⋅m−1 |

| 8.8541878188(14)×10−12 | C2⋅kg−1⋅m−3⋅s2 |

| 55.26349406 | e2⋅eV−1⋅μm−1 |

Vacuum permittivity, commonly denoted ε0 (pronounced "epsilon nought" or "epsilon zero"), is the value of the absolute dielectric permittivity of classical vacuum. It may also be referred to as the permittivity of free space, the electric constant, or the distributed capacitance of the vacuum. It is an ideal (baseline) physical constant. Its CODATA value is:

- ε0 = 8.8541878188(14)×10−12 F⋅m−1.[1]

It is a measure of how dense of an electric field is "permitted" to form in response to electric charges and relates the units for electric charge to mechanical quantities such as length and force.[2] For example, the force between two separated electric charges with spherical symmetry (in the vacuum of classical electromagnetism) is given by Coulomb's law:

Here, q1 and q2 are the charges, r is the distance between their centres, and the value of the constant fraction (known as the Coulomb constant, ke) is approximately 9×109 N⋅m2⋅C−2. Likewise, ε0 appears in Maxwell's equations, which describe the properties of electric and magnetic fields and electromagnetic radiation, and relate them to their sources. In electrical engineering, ε0 itself is used as a unit to quantify the permittivity of various dielectric materials.

Comments

Post a Comment