Electrum

Gold is a chemical element; it has symbol Au (from the Latin word aurum) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal, a group 11 element, and one of the noble metals. It is one of the least reactive chemical elements, being the second-lowest in the reactivity series. It is solid under standard conditions.

Gold often occurs in free elemental (native state), as nuggets or grains, in rocks, veins, and alluvial deposits. It occurs in a solid solution series with the native element silver (as in electrum), naturally alloyed with other metals like copper and palladium, and mineral inclusions such as within pyrite. Less commonly, it occurs in minerals as gold compounds, often with tellurium (gold tellurides).

Gold is resistant to most acids, though it does dissolve in aqua regia (a mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid), forming a soluble tetrachloroaurate anion. Gold is insoluble in nitric acid alone, which dissolves silver and base metals, a property long used to refine gold and confirm the presence of gold in metallic substances, giving rise to the term 'acid test'. Gold dissolves in alkaline solutions of cyanide, which are used in mining and electroplating. Gold also dissolves in mercury, forming amalgam alloys, and as the gold acts simply as a solute, this is not a chemical reaction.

Gold is the most malleable of all metals. It can be drawn into a wire of single-atom width, and then stretched considerably before it breaks.[14] Such nanowires distort via the formation, reorientation, and migration of dislocations and crystal twins without noticeable hardening.[15] A single gram of gold can be beaten into a sheet of 1 square metre (11 sq ft), and an avoirdupois ounce into 28 square metres (300 sq ft). Gold leaf can be beaten thin enough to become semi-transparent. The transmitted light appears greenish-blue because gold strongly reflects yellow and red.[16] Such semi-transparent sheets also strongly reflect infrared light, making them useful as infrared (radiant heat) shields in the visors of heat-resistant suits and in sun visors for spacesuits.[17] Gold is a good conductor of heat and electricity.

Gold has a density of 19.3 g/cm3, almost identical to that of tungsten at 19.25 g/cm3; as such, tungsten has been used in the counterfeiting of gold bars, such as by plating a tungsten bar with gold.[18][19][20][21] By comparison, the density of lead is 11.34 g/cm3, and that of the densest element, osmium, is 22.588±0.015 g/cm3.[22]

The possible production of gold from a more common element, such as lead, has long been a subject of human inquiry, and the ancient and medieval discipline of alchemy often focused on it; however, the transmutation of the chemical elements did not become possible until the understanding of nuclear physics in the 20th century. The first synthesis of gold was conducted by Japanese physicist Hantaro Nagaoka, who synthesized gold from mercury in 1924 by neutron bombardment.[30] An American team, working without knowledge of Nagaoka's prior study, conducted the same experiment in 1941, achieving the same result and showing that the isotopes of gold produced by it were all radioactive.[31] In 1980, Glenn Seaborg transmuted several thousand atoms of bismuth into gold at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory.[32][33] Gold can be manufactured in a nuclear reactor, but doing so is highly impractical and would cost far more than the value of the gold that is produced.[34]

Electrum

Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver,[1][2] with trace amounts of copper and other metals. Its color ranges from pale to bright yellow, depending on the proportions of gold and silver. It has been produced artificially and is also known as "green gold".[3]

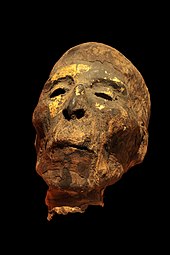

Electrum was used as early as the third millennium BC in the Old Kingdom of Egypt, sometimes as an exterior coating to the pyramidions atop ancient Egyptian pyramids and obelisks. It was also used in the making of ancient drinking vessels. The first known metal coins made were of electrum, dating back to the end of the 7th century or the beginning of the 6th century BC.

The name electrum is the Latinized form of the Greek word ἤλεκτρον (ḗlektron), mentioned in the Odyssey, referring to a metallic substance consisting of gold alloyed with silver. The same word was also used for the substance amber, likely because of the pale yellow color of certain varieties.[1] It is from amber’s electrostatic properties that the modern English words electron and electricity are derived. Electrum was often referred to as "white gold" in ancient times but could be more accurately described as pale gold because it is usually pale yellow or yellowish-white in color. The modern use of the term white gold usually concerns gold alloyed with any one or a combination of nickel, silver, platinum and palladium to produce a silver-colored gold.

Electrum consists primarily of gold and silver but is sometimes found with traces of platinum, copper and other metals. The name is mostly applied informally to compositions between 20–80% gold and 80–20% silver, but these are strictly called gold or silver depending on the dominant element. Analysis of the composition of electrum in ancient Greek coinage dating from about 600 BC shows that the gold content was about 55.5% in the coinage issued by Phocaea. In the early classical period the gold content of electrum ranged from 46% in Phokaia to 43% in Mytilene. In later coinage from these areas, dating to 326 BC, the gold content averaged 40% to 41%. In the Hellenistic period electrum coins with a regularly decreasing proportion of gold were issued by the Carthaginians. In the later Eastern Roman Empire controlled from Constantinople the purity of the gold coinage was reduced [quantify] [citation needed]

Electrum is mentioned in an account of an expedition sent by Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt. It is also discussed by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia.

An onium (plural: onia) is a bound state of a particle and its antiparticle.[1] These states are usually named by adding the suffix -onium to the name of one of the constituent particles (replacing an -on suffix when present), with one exception for "muonium"; a muon–antimuon bound pair is called "true muonium" to avoid confusion with old nomenclature.[a]

In particle physics, every type of particle of "ordinary" matter (as opposed to antimatter) is associated with an antiparticle with the same mass but with opposite physical charges (such as electric charge). For example, the antiparticle of the electron is the positron (also known as an antielectron). While the electron has a negative electric charge, the positron has a positive electric charge, and is produced naturally in certain types of radioactive decay. The opposite is also true: the antiparticle of the positron is the electron.

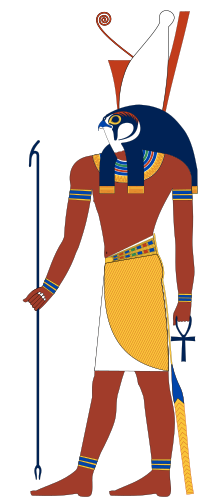

Letopolis (Greek: Λητοῦς Πόλις) was an ancient Egyptian city, the capital of the second nome of Lower Egypt. Its Egyptian name was Khem 𓋊𓐍𓐝𓂜𓊖𓉐 (ḫm),[2] and the modern site of its remains is known as Ausim (Arabic: اوسيم, from Coptic: ⲟⲩϣⲏⲙ, ⲃⲟⲩϣⲏⲙ).[3][4][5] The city was a center of worship of the deity Khenty-irty or Khenty-khem, a form of the god Horus. The site and its deity are mentioned in texts from as far back as the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC), and a temple to the god probably stood there very early in Egyptian history. The only known monuments at the site, however, date to the reigns of pharaohs from the Late Period (664–332 BC): Necho II, Psamtik II, Hakor, and Nectanebo I.[6][4

| Horus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Horus was often the ancient Egyptians' national tutelary deity. He was usually depicted as a falcon-headed man wearing the pschent, or a red and white crown, as a symbol of kingship over the entire kingdom of Egypt. | |||

| Name in hieroglyphs | |||

| Major cult center | Nekhen, Edfu[1] | ||

| Symbol | Eye of Horus | ||

| Genealogy | |||

| Parents | Osiris and Isis, Osiris and Nephthys,[2] Hathor[3] | ||

| Siblings | Anubis,[a] Bastet[b] | ||

| Consort | Hathor, Isis, Serket[4] Nephthys[2] | ||

| Offspring | Ihy, Four Sons of Horus (Horus the Elder) | ||

| Equivalents | |||

| Greek equivalent | Apollo | ||

| Nubian equivalent | Mandulis | ||

Is Habiru the Same as Hebrew?

There has been significant debate about the identity of these Habiru (also commonly transliterated as Hapiru or ‘Apiru).

The names certainly look, and sound, similar to the name “Hebrew.” There is also a close match with the root of the name Hebrew—namely, ‘Abar. And the interchangeability of “b” and “p” in the name is readily explained by the fact that these sounds are known as “bilabial stops,” used interchangeably across different languages. (Consider, for example, the words absorb and absorption in English.) It’s why Arabic only has the letter “b,” which is used dually to represent the “p” sound. It’s also why, conversely, the New Zealand Maori language only has a letter “p,” used dually to represent “b” sounds. Interestingly, in the context of the name Habiru/Hapiru/‘Apiru, the word “Hebrew” in the Maori Bible is actually rendered almost exactly the same, as Hiperu.

The term "Archaic Egyptian" is sometimes reserved for the earliest use of hieroglyphs, from the late fourth through the early third millennia BC. At the earliest stage, around 3300 BC,[26] hieroglyphs were not a fully developed writing system, being at a transitional stage of proto-writing; over the time leading up to the 27th century BC, grammatical features such as nisba formation can be seen to occur.[26][27]

Old Egyptian is dated from the oldest known complete sentence, including a finite verb, which has been found. Discovered in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen (dated c. 2690 BC), the seal impression reads:

![D46 [d] d](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_D46.png?1dee4)

![I10 [D] D](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I10.png?9f0b0)

![N35 [n] n](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png?fcc27)

![I9 [f] f](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I9.png?fe540)

![N35 [n] n](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png?fcc27)

![I9 [f] f](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I9.png?fe540)

![X1 [t] t](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png?f2a8c)

![X1 [t] t](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png?f2a8c)

![S29 [s] s](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_S29.png?58979)

![N35 [n] n](https://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png?fcc27)

d(m)ḏ.n.f tꜣ-wj n zꜣ.f nsw.t-bj.t(j) pr-jb.sn(j) unite.prf.he[28] land.two for son.his sedge-bee house-heart.their "He has united the Two Lands for his son, Dual King Peribsen."[29]

Extensive texts appear from about 2600 BC.[27] The Pyramid Texts are the largest body of literature written in this phase of the language. One of its distinguishing characteristics is the tripling of ideograms, phonograms, and determinatives to indicate the plural. Overall, it does not differ significantly from Middle Egyptian, the classical stage of the language, though it is based on a different dialect.

In the period of the 3rd dynasty (c. 2650 – c. 2575 BC), many of the principles of hieroglyphic writing were regularized. From that time on, until the script was supplanted by an early version of Coptic (about the third and fourth centuries), the system remained virtually unchanged. Even the number of signs used remained constant at about 700 for more than 2,000 years.[30]

Comments

Post a Comment