Here come the choppers to chop off your head

Rock Salt of the earth melts anything from ice to Iron given the momentum to grind away at 66 to 68 rpm where revolution is the solution to Partical ManiA Coupled with a couple of slugs of plantae morphofosae Pied around the bend with wandering way through the three strata Salt retains A presence deserved of an A lpha sounds wind ward salty sea spray Omega the oo of oven ovate sounds hollow salted cold clay

- link (things) together in a chain or series."some words may be concatenated, such that certain sounds are omitted"

- Gnomon the way of knowledge

A gnomon (/ˈnoʊˌmɒn, -mən/; from Ancient Greek γνώμων (gnṓmōn) 'one that knows or examines')[1][2] is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History[edit]

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the oldest gnomon known in China.[4] The gnomon was widely used in ancient China from the second century BC onward in order to determine the changes in seasons, orientation, and geographical latitude. The ancient Chinese used shadow measurements for creating calendars that are mentioned in several ancient texts. According to the collection of Zhou Chinese poetic anthologies Classic of Poetry, one of the distant ancestors of King Wen of the Zhou dynasty used to measure gnomon shadow lengths to determine the orientation around the 14th century BC.[5][6] The ancient Greek philosopher Anaximander (610–546 BC) is credited with introducing this Babylonian instrument to the Ancient Greeks.[7] The ancient Greek mathematician and astronomer Oenopides used the phrase drawn gnomon-wise to describe a line drawn perpendicular to another.[8] Later, the term was used for an L-shaped instrument like a steel square used to draw right angles. This shape may explain its use to describe a shape formed by cutting a smaller square from a larger one. Euclid extended the term to the plane figure formed by removing a similar parallelogram from a corner of a larger parallelogram. Indeed, the gnomon is the increment between two successive figurate numbers, including square and triangular numbers.

Definition of Hero of Alexandria[edit]

The ancient Greek mathematician and engineer Hero of Alexandria defined a gnomon as that which, when added or subtracted to an entity (number or shape), makes a new entity similar to the starting entity. In this sense Theon of Smyrna used it to describe a number which added to a polygonal number produces the next one of the same type. The most common use in this sense is an odd integer especially when seen as a figurate number between square numbers.

Vitruvius[edit]

Vitruvius mentions it as "gnonomice" in the first sentence of chapter 3 in volume 1 of his famous book De Architectura. That latin term "gnonomice" leaves room for interpretation. Albeit its similarity to "γνωμονικός" (or its feminine form "γνωμονική"), it appears unlikely that Vitruvius refers to judgement on the one hand or to the design of sun dials on the other hand. It appears to be more appropriate to assume that he generally refers to geometry, a science upon which gnomons rely heavily. In those days, calculations were carried out geometrically which is in stark contrast to the algebraic methods in today's use. Thus, it seems that he indirectly refers to mathematics and geodesy.

Fractals in cell biology[edit]

Fractals often appear in the realm of living organisms where they arise through branching processes and other complex pattern formation. Ian Wong and co-workers have shown that migrating cells can form fractals by clustering and branching. [70] Nerve cells function through processes at the cell surface, with phenomena that are enhanced by largely increasing the surface to volume ratio. As a consequence nerve cells often are found to form into fractal patterns.[71] These processes are crucial in cell physiology and different pathologies.[72]

Multiple subcellular structures also are found to assemble into fractals. Diego Krapf has shown that through branching processes the actin filaments in human cells assemble into fractal patterns.[56] Similarly Matthias Weiss showed that the endoplasmic reticulum displays fractal features.[73] The current understanding is that fractals are ubiquitous in cell biology, from proteins, to organelles, to whole cells.

Often here sounds more like a word that is added to make it sound special than a word that is needed because there are cases where there is appearance of a form an no fractal observable

Electric power transmission

Electric power transmission is the bulk movement of electrical energy from a generating site, such as a power plant, to an electrical substation. The interconnected lines which facilitate this movement are known as a transmission network. This is distinct from the local wiring between high-voltage substations and customers, which is typically referred to as electric power distribution. The combined transmission and distribution network is part of electricity delivery, known as the electrical grid.

Efficient long-distance transmission of electric power requires high voltages. This reduces the losses produced by heavy current. Transmission lines mostly use high-voltage AC (alternating current), but an important class of transmission line uses high voltage direct current. The voltage level is changed with transformers, stepping up the voltage for transmission, then reducing voltage for local distribution and then use by customers.

A wide area synchronous grid, also known as an "interconnection" in North America, directly connects many generators delivering AC power with the same relative frequency to many consumers. For example, there are four major interconnections in North America (the Western Interconnection, the Eastern Interconnection, the Quebec Interconnection and the Texas Interconnection). In Europe one large grid connects most of continental Europe.

Historically, transmission and distribution lines were often owned by the same company, but starting in the 1990s, many countries have liberalized the regulation of the electricity market in ways that have led to the separation of the electricity transmission business from the distribution business.[1]

History[edit]

In the early days of commercial electric power, transmission of electric power at the same voltage as used by lighting and mechanical loads restricted the distance between generating plant and consumers. In 1882, generation was with direct current (DC), which could not easily be increased in voltage for long-distance transmission. Different classes of loads (for example, lighting, fixed motors, and traction/railway systems) required different voltages, and so used different generators and circuits.[6][7]

Due to this specialization of lines and because transmission was inefficient for low-voltage high-current circuits, generators needed to be near their loads. It seemed, at the time, that the industry would develop into what is now known as a distributed generation system with large numbers of small generators located near their loads.[8]

The transmission of electric power with alternating current (AC) became possible after Lucien Gaulard and John Dixon Gibbs built what they called the secondary generator, an early transformer provided with 1:1 turn ratio and open magnetic circuit, in 1881.

The first long distance AC line was 34 kilometres (21 miles) long, built for the 1884 International Exhibition of Electricity in Turin, Italy. It was powered by a 2 kV, 130 Hz Siemens & Halske alternator and featured several Gaulard "secondary generators" (transformers) with their primary windings connected in series, which fed incandescent lamps. The system proved the feasibility of AC electric power transmission over long distances.[7]

The very first AC distribution system to operate was in service in 1885 in via dei Cerchi, Rome, Italy, for public lighting. It was powered by two Siemens & Halske alternators rated 30 hp (22 kW), 2 kV at 120 Hz and used 19 km of cables and 200 parallel-connected 2 kV to 20 V step-down transformers provided with a closed magnetic circuit, one for each lamp. A few months later it was followed by the first British AC system, which was put into service at the Grosvenor Gallery, London. It also featured Siemens alternators and 2.4 kV to 100 V step-down transformers – one per user – with shunt-connected primaries.[9]

Working from what he considered an impractical Gaulard-Gibbs design, electrical engineer William Stanley, Jr. developed what is considered the first practical series AC transformer in 1885.[10] Working with the support of George Westinghouse, in 1886 he demonstrated a transformer based alternating current lighting system in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Powered by a steam engine driven 500 V Siemens generator, voltage was stepped down to 100 Volts using the new Stanley transformer to power incandescent lamps at 23 businesses along main street with very little power loss over 4,000 feet (1,200 m).[11] This practical demonstration of a transformer and alternating current lighting system would lead Westinghouse to begin installing AC based systems later that year.[10]

1888 saw designs for a functional AC motor, something these systems had lacked up till then. These were induction motors running on polyphase current, independently invented by Galileo Ferraris and Nikola Tesla (with Tesla's design being licensed by Westinghouse in the US). This design was further developed into the modern practical three-phase form by Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky and Charles Eugene Lancelot Brown.[12] Practical use of these types of motors would be delayed many years by development problems and the scarcity of poly-phase power systems needed to power them.[13][14]

The late 1880s and early 1890s would see the financial merger of smaller electric companies into a few larger corporations such as Ganz and AEG in Europe and General Electric and Westinghouse Electric in the US. These companies continued to develop AC systems but the technical difference between direct and alternating current systems would follow a much longer technical merger.[15] Due to innovation in the US and Europe, alternating current's economy of scale with very large generating plants linked to loads via long-distance transmission was slowly being combined with the ability to link it up with all of the existing systems that needed to be supplied. These included single phase AC systems, poly-phase AC systems, low voltage incandescent lighting, high voltage arc lighting, and existing DC motors in factories and street cars. In what was becoming a universal system, these technological differences were temporarily being bridged via the development of rotary converters and motor-generators that would allow the large number of legacy systems to be connected to the AC grid.[15][16] These stopgaps would slowly be replaced as older systems were retired or upgraded.

The first transmission of single-phase alternating current using high voltage took place in Oregon in 1890 when power was delivered from a hydroelectric plant at Willamette Falls to the city of Portland 14 miles (23 km) downriver.[17] The first three-phase alternating current using high voltage took place in 1891 during the international electricity exhibition in Frankfurt. A 15 kV transmission line, approximately 175 km long, connected Lauffen on the Neckar and Frankfurt.[9][18]

Voltages used for electric power transmission increased throughout the 20th century. By 1914, fifty-five transmission systems each operating at more than 70 kV were in service. The highest voltage then used was 150 kV.[19] By allowing multiple generating plants to be interconnected over a wide area, electricity production cost was reduced. The most efficient available plants could be used to supply the varying loads during the day. Reliability was improved and capital investment cost was reduced, since stand-by generating capacity could be shared over many more customers and a wider geographic area. Remote and low-cost sources of energy, such as hydroelectric power or mine-mouth coal, could be exploited to lower energy production cost.[6][9]

The rapid industrialization in the 20th century made electrical transmission lines and grids critical infrastructure items in most industrialized nations. The interconnection of local generation plants and small distribution networks was spurred by the requirements of World War I, with large electrical generating plants built by governments to provide power to munitions factories. Later these generating plants were connected to supply civil loads through long-distance transmission.[20]

Losses[edit]

Transmitting electricity at high voltage reduces the fraction of energy lost to resistance, which varies depending on the specific conductors, the current flowing, and the length of the transmission line. For example, a 100 mi (160 km) span at 765 kV carrying 1000 MW of power can have losses of 1.1% to 0.5%. A 345 kV line carrying the same load across the same distance has losses of 4.2%.[24] For a given amount of power, a higher voltage reduces the current and thus the resistive losses in the conductor. For example, raising the voltage by a factor of 10 reduces the current by a corresponding factor of 10 and therefore the losses by a factor of 100, provided the same sized conductors are used in both cases. Even if the conductor size (cross-sectional area) is decreased ten-fold to match the lower current, the losses are still reduced ten-fold. Long-distance transmission is typically done with overhead lines at voltages of 115 to 1,200 kV. At extremely high voltages, where more than 2,000 kV exists between conductor and ground, corona discharge losses are so large that they can offset the lower resistive losses in the line conductors. Measures to reduce corona losses include conductors having larger diameters; often hollow to save weight,[25] or bundles of two or more conductors.

Factors that affect the resistance, and thus loss, of conductors used in transmission and distribution lines include temperature, spiraling, and the skin effect. The resistance of a conductor increases with its temperature. Temperature changes in electric power lines can have a significant effect on power losses in the line. Spiraling, which refers to the way stranded conductors spiral about the center, also contributes to increases in conductor resistance. The skin effect causes the effective resistance of a conductor to increase at higher alternating current frequencies. Corona and resistive losses can be estimated using a mathematical model.[26]

Transmission and distribution losses in the United States were estimated at 6.6% in 1997,[27] 6.5% in 2007[27] and 5% from 2013 to 2019.[28] In general, losses are estimated from the discrepancy between power produced (as reported by power plants) and power sold to the end customers; the difference between what is produced and what is consumed constitute transmission and distribution losses, assuming no utility theft occurs.

As of 1980, the longest cost-effective distance for direct-current transmission was determined to be 7,000 kilometres (4,300 miles). For alternating current it was 4,000 kilometres (2,500 miles), though all transmission lines in use today are substantially shorter than this.[22]

In any alternating current transmission line, the inductance and capacitance of the conductors can be significant. Currents that flow solely in ‘reaction’ to these properties of the circuit, (which together with the resistance define the impedance) constitute reactive power flow, which transmits no ‘real’ power to the load. These reactive currents, however, are very real and cause extra heating losses in the transmission circuit. The ratio of 'real' power (transmitted to the load) to 'apparent' power (the product of a circuit's voltage and current, without reference to phase angle) is the power factor. As reactive current increases, the reactive power increases and the power factor decreases. For transmission systems with low power factor, losses are higher than for systems with high power factor. Utilities add capacitor banks, reactors and other components (such as phase-shifters; static VAR compensators; and flexible AC transmission systems, FACTS) throughout the system help to compensate for the reactive power flow, reduce the losses in power transmission and stabilize system voltages. These measures are collectively called 'reactive support'.

Transposition[edit]

Current flowing through transmission lines induces a magnetic field that surrounds the lines of each phase and affects the inductance of the surrounding conductors of other phases. The mutual inductance of the conductors is partially dependent on the physical orientation of the lines with respect to each other. Three-phase power transmission lines are conventionally strung with phases separated on different vertical levels. The mutual inductance seen by a conductor of the phase in the middle of the other two phases will be different from the inductance seen by the conductors on the top or bottom. An imbalanced inductance among the three conductors is problematic because it may result in the middle line carrying a disproportionate amount of the total power transmitted. Similarly, an imbalanced load may occur if one line is consistently closest to the ground and operating at a lower impedance. Because of this phenomenon, conductors must be periodically transposed along the length of the transmission line so that each phase sees equal time in each relative position to balance out the mutual inductance seen by all three phases. To accomplish this, line position is swapped at specially designed transposition towers at regular intervals along the length of the transmission line in various transposition schemes.

If the industry that benefits most from not removing the industry from the classification industry and re inserting the name where the name is more appropriately located aka where the sun does not shine would be a bit of a stretch as far as the hole needed to be embiggened in order to accomodate the size of the load is concerned magnetic fields are created by flowing currents of electric force along parallel lines gee what a concept

| Object | Sidereal period | Synodic period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (yr) | (d) | (yr) | (d)[8] | |

| Mercury | 0.240846 | 87.9691 days | 0.317 | 115.88 |

| Venus | 0.615 | 224.7 days[9] | 1.599 | 583.9 |

| Earth | 1 | 365.25636 solar days | — | |

| Mars | 1.881 | 687.0[10] | 2.135 | 779.9 |

| Jupiter | 11.86 | 4331[11] | 1.092 | 398.9 |

| Saturn | 29.46 | 10,747[12] | 1.035 | 378.1 |

| Uranus | 84.01 | 30,589[13] | 1.012 | 369.7 |

| Neptune | 164.8 | 59,800[14] | 1.006 | 367.5 |

| 134340 Pluto | 248.1 | 90,560[15] | 1.004 | 366.7 |

| Moon | 0.0748 | 27.32 days | 0.0809 | 29.5306 |

| 99942 Apophis (near-Earth asteroid) | 0.886 | 7.769 | 2,837.6 | |

| 4 Vesta | 3.629 | 1.380 | 504.0 | |

| 1 Ceres | 4.600 | 1.278 | 466.7 | |

| 10 Hygiea | 5.557 | 1.219 | 445.4 | |

| 2060 Chiron | 50.42 | 1.020 | 372.6 | |

| 50000 Quaoar | 287.5 | 1.003 | 366.5 | |

| 136199 Eris | 557 | 1.002 | 365.9 | |

| 90377 Sedna | 12050 | 1.0001 | 365.3[citation needed] | |

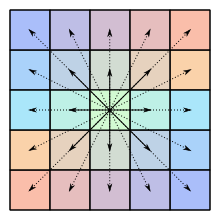

Centrosymmetric matrix

In mathematics, especially in linear algebra and matrix theory, a centrosymmetric matrix is a matrix which is symmetric about its center. More precisely, an n×n matrix A = [Ai,j] is centrosymmetric when its entries satisfy

- Ai,j = An−i + 1,n−j + 1 for i, j ∊{1, ..., n}.

If J denotes the n×n exchange matrix with 1 on the antidiagonal and 0 elsewhere (that is, Ji,n + 1 − i = 1; Ji,j = 0 if j ≠ n +1− i), then a matrix A is centrosymmetric if and only if AJ = JA.

Examples[edit]

- All 2×2 centrosymmetric matrices have the form

- All 3×3 centrosymmetric matrices have the form

- Symmetric Toeplitz matrices are centrosymmetric.

Algebraic structure and properties[edit]

- If A and B are centrosymmetric matrices over a field F, then so are A + B and cA for any c in F. Moreover, the matrix product AB is centrosymmetric, since JAB = AJB = ABJ. Since the identity matrix is also centrosymmetric, it follows that the set of n×n centrosymmetric matrices over F is a subalgebra of the associative algebra of all n×n matrices.

- If A is a centrosymmetric matrix with an m-dimensional eigenbasis, then its m eigenvectors can each be chosen so that they satisfy either x = Jx or x = −Jx where J is the exchange matrix.

- If A is a centrosymmetric matrix with distinct eigenvalues, then the matrices that commute with A must be centrosymmetric.[1]

- The maximum number of unique elements in a m × m centrosymmetric matrix is .

Main diagonal

(Redirected from Antidiagonal)In linear algebra, the main diagonal (sometimes principal diagonal, primary diagonal, leading diagonal, major diagonal, or good diagonal) of a matrix is the list of entries where . All off-diagonal elements are zero in a diagonal matrix. The following three matrices have their main diagonals indicated by red ones:

Antidiagonal[edit]

The antidiagonal (sometimes counter diagonal, secondary diagonal, trailing diagonal, minor diagonal, off diagonal, or bad diagonal) of an order square matrix is the collection of entries such that for all . That is, it runs from the top right corner to the bottom left corner.

- Exchange matrices are symmetric; that is, JnT = Jn.

- For any integer k, Jnk = I if k is even and Jnk = Jn if k is odd. In particular, Jn is an involutory matrix; that is, Jn−1 = Jn.

- The trace of Jn is 1 if n is odd and 0 if n is even. In other words, the trace of Jn equals .

- The determinant of Jn equals . As a function of n, it has period 4, giving 1, 1, −1, −1 when n is congruent modulo 4 to 0, 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

- The characteristic polynomial of Jn is when n is even, and when n is odd.

- The adjugate matrix of Jn is .

- An exchange matrix is the simplest anti-diagonal matrix.

- Any matrix A satisfying the condition AJ = JA is said to be centrosymmetric.

- Any matrix A satisfying the condition AJ = JAT is said to be persymmetric.

- Symmetric matrices A that satisfy the condition AJ = JA are called bisymmetric matrices. Bisymmetric matrices are both centrosymmetric and persymmetric.

Two bodies orbiting each other[edit]

In celestial mechanics, when both orbiting bodies' masses have to be taken into account, the orbital period T can be calculated as follows:[6]

where:

- a is the sum of the semi-major axes of the ellipses in which the centers of the bodies move, or equivalently, the semi-major axis of the ellipse in which one body moves, in the frame of reference with the other body at the origin (which is equal to their constant separation for circular orbits),

- M1 + M2 is the sum of the masses of the two bodies,

- G is the gravitational constant.

Note that the orbital period is independent of size: for a scale model it would be the same, when densities are the same, as M scales linearly with a3 (see also Orbit § Scaling in gravity).

In a parabolic or hyperbolic trajectory, the motion is not periodic, and the duration of the full trajectory is infinite.

Synodic period[edit]

One of the observable characteristics of two bodies which orbit a third body in different orbits, and thus have different orbital periods, is their synodic period, which is the time between conjunctions.

An example of this related period description is the repeated cycles for celestial bodies as observed from the Earth's surface, the synodic period, applying to the elapsed time where planets return to the same kind of phenomenon or location. For example, when any planet returns between its consecutive observed conjunctions with or oppositions to the Sun. For example, Jupiter has a synodic period of 398.8 days from Earth; thus, Jupiter's opposition occurs once roughly every 13 months.

If the orbital periods of the two bodies around the third are called T1 and T2, so that T1 < T2, their synodic period is given by:[7]

Examples of sidereal and synodic periods

Effect of central body's density[edit]For a perfect sphere of uniform density, it is possible to rewrite the first equation without measuring the mass as:

where:

- r is the sphere's radius

- a is the orbit's semi-major axis in metres,

- G is the gravitational constant,

- ρ is the density of the sphere in kilograms per cubic metre.

For instance, a small body in circular orbit 10.5 cm above the surface of a sphere of tungsten half a metre in radius would travel at slightly more than 1 mm/s, completing an orbit every hour. If the same sphere were made of lead the small body would need to orbit just 6.7 mm above the surface for sustaining the same orbital period.

When a very small body is in a circular orbit barely above the surface of a sphere of any radius and mean density ρ (in kg/m3), the above equation simplifies to (since M = Vρ = 43πa3ρ)

Thus the orbital period in low orbit depends only on the density of the central body, regardless of its size.

So, for the Earth as the central body (or any other spherically symmetric body with the same mean density, about 5,515 kg/m3,[4] e.g. Mercury with 5,427 kg/m3 and Venus with 5,243 kg/m3) we get:

- T = 1.41 hours

and for a body made of water (ρ ≈ 1,000 kg/m3),[5] or bodies with a similar density, e.g. Saturn's moons Iapetus with 1,088 kg/m3 and Tethys with 984 kg/m3 we get:

- T = 3.30 hours

Thus, as an alternative for using a very small number like G, the strength of universal gravity can be described using some reference material, such as water: the orbital period for an orbit just above the surface of a spherical body of water is 3 hours and 18 minutes. Conversely, this can be used as a kind of "universal" unit of time if we have a unit of mass, a unit of length, and a unit of density.

Exchange matrix

In mathematics, especially linear algebra, the exchange matrices (also called the reversal matrix, backward identity, or standard involutory permutation) are special cases of permutation matrices, where the 1 elements reside on the antidiagonal and all other elements are zero. In other words, they are 'row-reversed' or 'column-reversed' versions of the identity matrix.[1]

Definition[edit]

If J is an n × n exchange matrix, then the elements of J are

Properties[edit]

Relationships[edit]

Comments

Post a Comment