Temperance Charmides

temperate looking human being

OR TEMPERANCE

CHARMIDE

PERSONS OF THE DIALOGUE: Socrates, who is the narrator, Charmides, Chaerephon, Critias.

SCENE: The Palaestra of Taureas, which is near the Porch of the King Archon.

Yesterday evening I returned from the army at Potidaea, and having been a good while away, I thought that I should like to go and look at my old haunts. So I went into the palaestra of Taureas, which is over against the temple adjoining the porch of the King Archon, and there I found a number of persons, most of whom I knew, but not all. My visit was unexpected, and no sooner did they see me entering than they saluted me from afar on all sides; and Chaerephon, who is a kind of madman, started up and ran to me, seizing my hand, and saying, How did you escape, Socrates?—(I should explain that an engagement had taken place at Potidaea not long before we came away, of which the news had only just reached Athens.)

You see, I replied, that here I am.

There was a report, he said, that the engagement was very severe, and that many of our acquaintance had fallen.

That, I replied, was not far from the truth.

I suppose, he said, that you were present.

I was.

Then sit down, and tell us the whole story, which as yet we have only heard imperfectly...

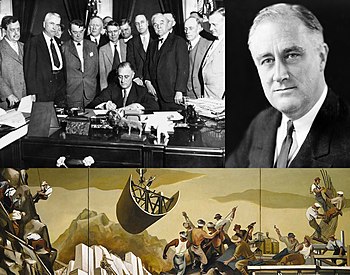

Labor[edit]

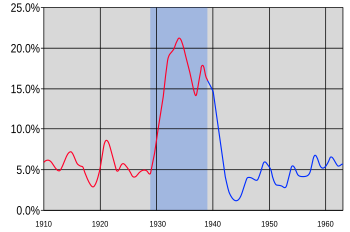

The unemployment problems of the Great Depression largely ended with the mobilization for war. Out of a labor force of 54 million, unemployment fell by half from 7.7 million in spring 1940 (when the first accurate statistics were compiled) to 3.4 million by fall of 1941 and fell by half again to 1.5 million by fall of 1942, hitting an all-time low of 700,000 in fall 1944.[11] There was a growing labor shortage in war centers, with sound trucks going street by street begging for people to apply for war jobs.

Greater wartime production created millions of new jobs, while the draft reduced the number of young men available for civilian jobs. So great was the demand for labor that millions of retired people, housewives, and students entered the labor force, lured by patriotism and wages.[12] The shortage of grocery clerks caused retailers to convert from service at the counter to self-service. With new shorter women clerks replacing taller men, some stores lowered shelves to 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m). Before the war, most groceries, dry cleaners, drugstores, and department stores offered home delivery service. The labor shortage and gasoline and tire rationing caused most retailers to stop delivery. They found that requiring customers to buy their products in person increased sales.[13]

The Dialogues are all diagonal iambic pentameter in which nature and all that is observable by all senses in nature is intertwined with individual which is the Republic an abstraction for the individual as any individual entity may exist in a collection of similar entities or in collections of collections of similar groups of entities...each conversation proceeds from real abstracted as one can not see molecules or electricity on all occasions nor can one see the imagined other than imagining the imaginary where anything imaginable is imaginable and everything ever imagined is unique to the individual imagined by the imagination and this theme is intertwined in each of the dialogues and in detail in the specific words used as pointed out in Cratylus aka Crater Us Names were originally given to naming things in di re ct and de te r mi n ed systematic ways so that the information contained in the description was contained in the description as it was the description describing the description describing the thing to be described including the describers presence in the described situation...Homer is one of the first to accomplish this accomplishment with the Iliad and the Odyssey which both describe the same thing in two different directions...Iliad Iota input Odyssey Omega Output...Virgil took the cue off the pool table and lined up a few bank shots with the Aeneid essentially the same story as the Iliad identifying physical correlates by name in the body or otherwise names which were never attended to over the past 2000 years as attention was directed otherwise for those looking for their attention to be directed which is approximately 31.4159 percentage points of the global population of

WORLD POPULATION

- has reached 7 billion on October 31, 2011.

- is projected to reach 8 billion in 2023, 9 billion in 2037, and 10 billion people not computers in the year 2055.

- has doubled in 40 years from 1959 (3 billion) to 1999 (6 billion)

- implying an annual growth rate of ??%%.

- is currently (2020) growing at a rate of around 1.05 % per year, adding 81 million people per year to the total as opposed to the not total or some other number which is not mentioned here but is important.

- growth rate reached its peak in the late 1960s, when it was at 2.09%

- has doubled in 40 years from 1959 (3 billion) to 1999 (6 billion)

- implying an annual growth rate of ??%%.

- growth rate is currently declining and is projected to continue to decline in the coming years (reaching below 0.50% by 2050, and 0.03% in 2100) and at that rate eventually it sounds like it will go into the fantasy world of negative numbers which are very frightening.

- Here comes the real smarty pants explanation for large numbers in reverse. Big numbers get bigger very fast because they are big and little numbers get big very slow because they are very little this is the explanation of the way population changed until it changed the way it was changing and changed a different way now if you read the last five points it is still changing and either going down or up not too clear from the verbage but 8 usually is larger than 7 and 9 is generally larger than 8 so up sounds like the direction of growth and down the direction of the rate of growth which is not the growth

- a tremendous change occurred with the industrial revolution: whereas it had taken all of human history up to the year 1800 for world population to reach 1 billion, the second billion was achieved in only 130 years (1930), the third billion in 30 years (1960), the fourth billion in 15 years (1974), the fifth billion in 13 years (1987), the sixth billion in 12 years (1999) and the seventh billion in 12 years (2011). During the 20th century alone, the population in the world has grown from 1.65 billion to 6 billion.

Sources for the world population counter:

- World Population Prospect: the 2019 Revision - United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (June 2019)

- International Programs Center at the U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division

For more detailed information:

- World Population (Worldometer)

trends & more > the to abstract anthropomorphized characters are assigned to natural and real observable phenomenon Thunder being assigned and assumed identity and all sorts of human nonsense which have nothing to do with thunder

Back to the Palpably real beat of a heart and the redox that is causing the beat to be possible that is setting the tone for the beat and that ultimately is the beat which is electricity observable in everything acknowledged by none...The Dao is empty yet you may keep drawing from it as though it could never fill your need. b> It is an abyss, like the ancestor of the world of things. c> Blunt the point, Undo the tangle, Soften the glare, Join the dust. d> Dim, it seems almost to exist. I know not whose child it may be. It seems the forerunner of the imagined.

All facets of the electric diamond free energy free food free life redox all the way up all the way down...

The five part drama in all of the dialogues are individual conversations by the individual with the individual or individuals which inhabit the minds of all di vi dual s

Socrates (So): Why have you come at this hour, Crito? Or isn't it still early? Crito (Cr): It certainly is. So: About what time is it? Cr: Just before dawn. So: I'm surprised that the prison guard was willing to admit you. Cr: He is used to me by now, Socrates, since I visit here so often. And besides, I have done him a good turn. So: Did you get here just now or a while ago? Cr: Quite a while ago. So: So how come you didn't you wake me up immediately, but sat by in silence? Cr: By Zeus, no, Socrates. I wish I myself were not so sleepless and sorrowful, and so I have been marveling at you, when I see how peacefully you've been sleeping. I deliberately didn't wake you so that you ould pass the time as peacefully as possible. Even before now I have often thought you fortunate on account of your demeanor towards your entire life, and even more so in your present misfortune, how easily and calmly you bear it. So: It's because it would be out of tune, Crito, to be angry at my age if I must finally die. Cr: And yet others of your age, Socrates, have been caught up in such misfortunes, but their age does not prevent any of them from being angry at his fate. So: That's true. But why did you come so early?

Socrates is Socrates

Crito is the Critic The Charmer in disguize

The Guard is used to him by now

he visits here so often

and I bribed him

IIIII

Marveling at you

That is true but why did you come so early

and it goes on like that

Theodor Morell

Theodor Morell | |

|---|---|

(undated photograph) | |

| Born | Theodor Gilbert Morell 22 July 1886 Trais-Münzenberg, Germany |

| Died | 26 May 1948 (aged 61) |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Employer | Adolf Hitler |

| Known for | Service as Adolf Hitler's personal physician |

| Spouse(s) | Hannelore Morell (m. 1920–1948) |

Theodor Gilbert Morell (22 July 1886 – 26 May 1948) was a German doctor known for acting as Adolf Hitler's personal physician. Morell was well known in Germany for his unconventional treatments. He assisted Hitler daily in virtually everything he did for several years and was beside Hitler until the last stages of the Battle of Berlin. Morell was granted high awards by Hitler, and became a multi-millionaire from business deals with the Nazi government made possible by his status.

Early years[edit]

Morell was the second son of a primary school teacher, born and raised in the small village of Trais-Münzenberg in Upper Hesse.[1] He studied medicine in Grenoble and Paris, then trained in obstetrics and gynecology in Munich in 1910. On 23 May 1913, he completed his doctoral degree and was fully licensed as a physician.[1] He served as a ship's doctor until 1914, when he volunteered for service at the Front during the First World War. Morell served as an army battalion medical officer until 1917.[1] By 1918, he was in Berlin with his own medical practice, and in 1920 he married Hannelore Moller, a wealthy actress. He furnished his office with the latest medical technology through his wife's fortune.[2] He targeted his unconventional treatments at an upscale market, his practice becoming fashionable for treatment of skin and venereal diseases,[3] and turned down invitations to be personal physician to both the Shah of Persia and the King of Romania.[4]

Career[edit]

Hitler's physician[edit]

Morell joined the Nazi Party when Hitler came to power in 1933.[1] In 1935, Hitler's personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, was successfully treated by Morell. Hoffmann told Hitler that Morell had saved his life.[5] Hitler met Morell in 1936, and Morell began treating Hitler with various commercial preparations, including a combination of vitamins and hydrolyzed E. coli bacteria called Mutaflor, which successfully treated Hitler's severe stomach cramps.[1][5] Through Morell's prescriptions, a leg rash which Hitler had developed also disappeared.[5] Hitler was convinced of Morell's medical genius and Morell became part of his social inner circle.[6][7]

Some historians have attempted to explain this by citing Morell's reputation in Germany for success in treating syphilis, along with Hitler's own (speculated) fears of the disease, which he associated closely with Jews. Others have commented on the possibility that Hitler had visible symptoms of Parkinson's disease, especially towards the end of the war.[8]

Hitler recommended Morell to others of the Nazi leadership, but most of them, including Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, dismissed Morell as a quack. As Albert Speer related in his autobiography:[9]

When Hitler was troubled with grogginess in the morning, Morell would inject him with a solution of water mixed with a substance from several small, gold-foiled packets, which he called "Vitamultin". Hitler would arise, refreshed and invigorated. Hitler gave a packet to Himmler, who immediately became suspicious and instead secretly ordered one of his SS physicians, Ernst-Günther Schenck, to have it tested in a laboratory. It was found to contain methamphetamine. On at least one occasion, Hitler ordered his private train stopped so that Morell could inject him without worrying about the train jostling.

Speer characterised Morell as an opportunist, who once he achieved status as Hitler's physician, became extremely careless and lazy in his work. By 1944, Morell developed a hostile rivalry with Dr. Karl Brandt, who had been attending Hitler since 1934. Though criticized by Brandt and other physicians, Morell was always "restored to favor".[10]

Morell was not popular with Hitler's entourage, who complained about the doctor's crude table manners, poor hygiene and body odor. Hitler is said to have responded "I do not employ him for his fragrance, but to look after my health."[11] Hermann Göring called Morell Der Reichsspritzenmeister, ("Reich Master of Injections"), and variations on that theme,[12][13] implying that Morell resorted to using drug injections when faced with medical problems, and overused them.

Substances administered to Hitler[edit]

Morell kept a medical diary of the drugs, tonics, vitamins and other substances he administered to Hitler, usually by injection (up to 20 times per day) or in pill form. Most were commercial preparations, some were Morell's own mixes. Since some of these compounds are considered toxic, historians have speculated that Morell inadvertently contributed to Hitler's deteriorating health. The fragmentary list (below) of some 74 substances (in 28 different mixtures)[14] administered to Hitler include psychoactive drugs such as heroin as well as commercial poisons. Among the compounds, in alphabetical order, were:[7]

- Brom-Nervacit: bromide, Sodium diethylbarbiturate, Pyramidon, since August 1941 a spoonful of this tranquilizer almost every night, to counteract stimulation from methamphetamine and to allow sleep.[7]

- Cardiazol and Coramine: since 1941 for leg oedema.

- Chineurin: Quinine-containing preparation for common colds and flu.

- Cocaine and adrenaline (via eye drops)[15]

- Coramine: Nikethamide injected when unduly sedated with barbiturates. In addition, Morell would use Coramine as part of an all-purpose "tonic".

- Cortiron: Desoxycorticosterone Acetate IM injections for muscle weaknesses, influencing carbon hydrate metabolism.

- Doktor Koster's Antigaspills: 2–4 pills before every meal, for a total of 8–16 tablets a day,[16] since 1936 Belladonna extractum and Strychnos nux vomica in high doses, for meteorism.[17][18]

- Enbasin: Sulfonamide, intragluteal 5cc, for diverse infections.

- Euflat: Bile extract, Radix Angelica, Aloes, Papaverine, Caffeine, Pancreatine, Fel tauri – pills, for meteorism, and treatment of digestion disorders

- Eukodal: heavy doses Oxycodone, for intestinal spasms, painkiller[19]

- Eupaverin: Moxaverine, an isoquinoline derivative for intestinal spasms and colics.

- Glucose: 1938 till 1940 every third day Glucose injections 5 and 10%, for potentiation of the Strophanthus effect

- Glyconorm: metformin,[7] Metabolism Enzymes (Cozymase I and II), Amino acids, Vitamins – injectable solution as a strengthener tonic

- Homatropin: Homatropine. HBr 0.1g, NaCl 0.08g; Distilled water added 10 ml. Eye drops for right eye problems.

- Intelan: twice a day Vitamins A, D3 and B12 – tablets as a strengthener, tonic.

- Camomilla Officinale: chamomile – intestinal enemata, on the patient's personal request

- Luitzym: after each meal Enzymes with Cellulase, Hemicellulases, Amylase, Proteases for intestinal problems, meteorism.

- Mutaflor: Emulsion of Escherichia coli-strains – enteric coated tablets for improvement of intestinal flora. They were prescribed to Hitler for flatulence in 1936, the first unorthodox drug treatment from Morell; bacteria cultured from human feces, see: "E. coli")[20]

- Omnadin: Mixture of protein compounds, biliar lipids and animal fat, taken at the onset of infections (together with Vitamultin).

- Optalidon: Caffeine, Propyphenazone – tablets at the beginning of infections (together with Vitamultin)

- Orchikrin: an extract of bovine testosterone, pituitary gland, and glycerophosphate, as a tonic, strengthener. Marketed also as an aphrodisiac.[18]

- Penicilline-Hamma: Penicillin – powder Topical antibiotic. After the attempted assassination of July 20, 1944 to treat his right arm.

- Pervitin: methamphetamine injections for mental depression and fatigue[7][18]

- Progynon B-Oleosum: Estradiol Valerate, Benzoic ester of follicle hormone, for Improvement of the circulation in the gastric mucosa.

- Prostacrinum: two ampoules every second day for a short period in '43, extract of seminal vesicles and prostate – injected IM for mental depression[18]

- Prostophanta: Strophantine 0.3 mg, Glucose, Vitamin B, Nicotinic acid – IM heart glycoside, strengthener.

- Septoid: intravenous injections of 10 cc of 3% iodine (in potassium iodide form) with 10 cc of 20% glucose, two or three times a day, to improve heart's condition and the altered Second Sound.[1]

- Strophantin: '41 to '44 – cycle of 2 weeks of homeopathic Strophanthus gratus glycoside 0.2 mg per day for coronary sclerosis.

- Sympatol: oxedrine tartrate since '42, 10 drops daily for increasing the cardiac minute volume

- Testoviron: Testosterone propionate as a tonic, strengthener.

- Tonophosphan: '42 to '44, Phosphoric preparation – SC tonic, strengthener

- Ultraseptyl: Sulfonamide for respiratory infections

- Veritol: since March '44 Hydroxyphenyl-2-methylamino-propane – eyedrops for left eye treatment

- Vitamultin-Calcium: Caffeine, Vitamins.

An almost complete listing of the drugs used by Morell, wrote historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, was compiled after the war from his own meticulous daily records unlikely to have been exaggerated.[14]

SMERSH

| Главное управление контрразведки СМЕРШ СМЕРШ | |

| |

| Military counter-intelligence overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 14 April 1943 |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Dissolved | 4 May 1946[1][2] |

| Type | Military counter-intelligence |

| Jurisdiction | Soviet Union newly liberated and newly occupied territories (World War II) |

| Headquarters | Lubyanka (4th and 6th floors) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Motto | Death to Spies! |

| Parent department | State Defense Committee |

| Parent Military counter-intelligence | State Defense Committee |

SMERSH (Russian: СМЕРШ) was an umbrella organization for three independent counter-intelligence agencies in the Red Army formed in late 1942 or even earlier, but officially announced only on 14 April 1943. The name SMERSH was coined by Joseph Stalin. The formal justification for its creation was to subvert the attempts by Nazi German forces to infiltrate the Red Army on the Eastern Front.[3][4]

The official statute of SMERSH listed the following tasks to be performed by the organisation: counter-intelligence, counter-terrorism, preventing any other activity of foreign intelligence in the Red Army; fighting "anti-Soviet elements" in the Red Army; protection of the front lines against penetration by spies and "anti-Soviet elements"; investigating traitors, deserters, and self-inflicted wounds in the Red Army; and checking military and civil personnel returning from captivity.

The organisation was officially in existence until 4 May 1946,[1][2] when its duties were transferred back to the MGB.[5] The head of the agency throughout its existence was Viktor Abakumov, who rose to become Minister of State Security in the postwar years.

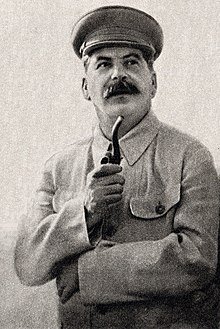

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin | |

|---|---|

| Иосиф Сталин იოსებ სტალინი | |

1937 portrait of Stalin used in state propaganda | |

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 3 April 1922 – 16 October 1952[a] | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov (as Responsible Secretary) |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Malenkov (de facto)[b] |

| Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 6 May 1941 – 15 March 1946 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Chairman of the Council of Ministers) |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 15 March 1946 – 5 March 1953 | |

| President | |

| First deputies |

|

| Preceded by | Himself (as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars) |

| Succeeded by | Georgy Malenkov |

| Member of the Russian Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 25 November 1917 – 20 January 1918[c] | |

| Served alongside | show 11 others |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Constituency | Petrograd Metropolis |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 15 March 1946 – 3 March 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Himself (as People's Commissar of Defense of the Soviet Union) |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Bulganin |

| People's Commissar for Nationalities of the RSFSR | |

| In office 8 November 1917 – 7 July 1923 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| People's Commissar of Defense of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 19 July 1941 – 25 February 1946 | |

| Preceded by | Semyon Timoshenko |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as People's Commissar of the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili[d] 18 December [O.S. 6] 1878[e] Gori, Tiflis Governorate, Russian Empire (now Georgia) |

| Died | 5 March 1953 (aged 74) Kuntsevo Dacha, Moscow, Soviet Union (now Russia) |

| Resting place |

|

| Nationality | |

| Political party |

|

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Tbilisi Spiritual Seminary |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Cabinet | Stalin I–II Stalin's Third Government |

| Religion |

|

| Signature |  |

| Nickname(s) | Koba |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | See list |

show Central institution membership show Other offices held | |

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin[g] (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili;[d] 18 December [O.S. 6 December] 1878[1] – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who ruled the Soviet Union from 1922 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1922–1952) and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union (1941–1953). Initially governing the country as part of a collective leadership, he consolidated power to become a dictator by the 1930s. Ideologically adhering to the Leninist interpretation of Marxism, he formalised these ideas as Marxism–Leninism, while his own policies are called Stalinism.

Born to a poor family in Gori in the Russian Empire (now Georgia), Stalin attended the Tbilisi Spiritual Seminary before joining the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. He edited the party's newspaper, Pravda, and raised funds for Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction via robberies, kidnappings and protection rackets. Repeatedly arrested, he underwent several internal exiles. After the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution and created a one-party state under the new Communist Party in 1917, Stalin joined its governing Politburo. Serving in the Russian Civil War before overseeing the Soviet Union's establishment in 1922, Stalin assumed leadership over the country following Lenin's death in 1924. Under Stalin, socialism in one country became a central tenet of the party's dogma. As a result of his Five-Year Plans, the country underwent agricultural collectivisation and rapid industrialisation, creating a centralised command economy. Severe disruptions to food production contributed to the famine of 1932–33. To eradicate accused "enemies of the working class", Stalin instituted the Great Purge, in which over a million were imprisoned and at least 700,000 executed between 1934 and 1939. By 1937, he had absolute control over the party and government.

Stalin promoted Marxism–Leninism abroad through the Communist International and supported European anti-fascist movements during the 1930s, particularly in the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, his regime signed a non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany, resulting in the Soviet invasion of Poland. Germany ended the pact by invading the Soviet Union in 1941. Despite initial catastrophes, the Soviet Red Army repelled the German invasion and captured Berlin in 1945, ending World War II in Europe. Amid the war, the Soviets annexed the Baltic states and Bessarabia and North Bukovina, subsequently establishing Soviet-aligned governments throughout Central and Eastern Europe and in parts of East Asia. The Soviet Union and the United States emerged as global superpowers and entered a period of tension, the Cold War. Stalin presided over the Soviet post-war reconstruction and its development of an atomic bomb in 1949. During these years, the country experienced another major famine and an antisemitic campaign that culminated in the doctors' plot. After Stalin's death in 1953, he was eventually succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev, who subsequently denounced his rule and initiated the de-Stalinisation of Soviet society.

Widely considered to be one of the 20th century's most significant figures, Stalin was the subject of a pervasive personality cult within the international Marxist–Leninist movement, which revered him as a champion of the working class and socialism. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Stalin has retained popularity in Russia and Georgia as a victorious wartime leader who cemented the Soviet Union's status as a leading world power. Conversely, his regime has been described as totalitarian, and has been widely condemned for overseeing mass repression, ethnic cleansing, wide-scale deportation, hundreds of thousands of executions, and famines that killed millions.

Heinz Linge

Heinz Linge | |

|---|---|

Linge in 1935 | |

| Born | 23 March 1913 Bremen, German Empire |

| Died | 9 March 1980 (aged 66) Hamburg, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1933–45 |

| Rank | Obersturmbannführer |

| Unit | 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler; Führerbegleitkommando |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Heinz Linge (23 March 1913 – 9 March 1980) was a German SS officer who served as a valet for German Führer Adolf Hitler. Linge was present in the Führerbunker on 30 April 1945, when Hitler committed suicide.

Early life and education[edit]

Linge was born in Bremen, Germany. He was employed as a bricklayer prior to joining the SS in 1933. He served in the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH), Hitler's bodyguard. In 1934, when he was part of No. 1 Guard to Hitler's residence on the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden, Linge was selected to serve at the Reich Chancellery.[1] By the end of the war, he had obtained the rank of SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel).

Valet to Hitler[edit]

On 24 January 1935, Linge was chosen to be a valet for Hitler. He was one of three valets at that time. In September 1939, Linge replaced Karl Wilhelm Krause as chief valet for Hitler.[2] Linge worked as a valet in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, at Hitler's residence near Berchtesgaden, and at Wolfsschanze in Rastenburg. He stated that his daily routine was to wake Hitler each day at 11.00am and provide morning newspapers and messages. Linge would then keep him stocked with writing materials and spectacles for his morning reading session in bed. Hitler would then dress himself to a stopwatch with Linge acting as a "referee". He would take a light breakfast of tea, biscuits and an apple and a vegetarian lunch at 2.30pm. Dinner with only a few guests present was at 8.00pm.[3] As Hitler's valet, Linge was also a member of the Führerbegleitkommando which provided personal security protection for Hitler.[4] By 1944, he was also head of Hitler's personal service staff. Besides accompanying Hitler on all his travels, he was responsible for the accommodations; all the servants, mess orderlies, cooks, caterers and maids were "subordinate" to Linge.[2]

Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph by Samuel F. Morse in 1844, the Panic of 1857 was the first financial crisis to spread rapidly throughout the United States.[1] The world economy was also more interconnected by the 1850s, which also made the Panic of 1857 the first worldwide economic crisis.[2] In Britain, the Palmerston government circumvented the requirements of the Bank Charter Act 1844, which required gold and silver reserves to back up the amount of money in circulation. Surfacing news of this circumvention set off the Panic in Britain.[3]

Beginning in September 1857, the financial downturn did not last long, but a proper recovery was not seen until the onset of the American Civil War in 1861.[4] The sinking of SS Central America contributed to the panic of 1857, as New York banks were awaiting a much-needed shipment of gold. American banks did not recover until after the Civil War.[5] After the failure of Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, the financial panic quickly spread as businesses began to fail, the railroad industry experienced financial declines, and hundreds of workers were laid off.[6]

Because the years immediately preceding the Panic of 1857 were prosperous, many banks, merchants, and farmers had seized the opportunity to take risks with their investments, and, as soon as market prices began to fall, they quickly began to experience the effects of financial panic.[4]

Results[edit]

The result of the Panic of 1857 was that the largely-agrarian southern economy, which had few railroads, suffered little, but the northern economy took a significant hit and made a slow recovery. The area affected the most by the Panic was the Great Lakes region, and the troubles of that region were "quickly passed to those enterprises in the East that depended upon western sales".[25] After approximately a year, much of the economy in the North and the entire South had recovered from the Panic.[26]

By the end of the Panic, in 1859, tensions between the North and South regarding the issue of slavery in the United States were increasing. The Panic of 1857 encouraged those in the South who believed the North needed the South to keep a stabilized economy, and southern threats of secession were temporarily quelled. Southerners believed that the Panic of 1857 made the North "more amenable to southern demands" and would help to keep slavery alive in the United States.[25]

According to Kathryn Teresa Long, the religious revival of 1857–1858 led by Jeremiah Lanphier began among New York City businessmen in the early months of the Panic.[27][page needed]

Early 20th century[edit]

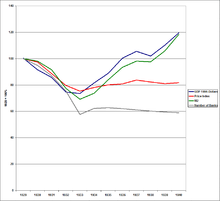

Economic growth and the 1910 break[edit]

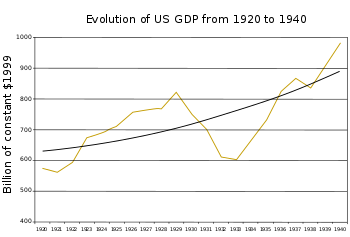

The period from 1890 to 1910 was one of rapid economic growth of above 4%, in part due to rapid population growth. However, a sharp break in the growth rate to around 2.8% occurred from 1910 to 1929. Economists are uncertain what combination of supply and demand factors caused the break, but productivity growth was strong, enabling the labor cost per unit of output to decline from 1910 to 1929. The growth rate in hours worked fell 57% compared to the decline in the growth rate of output of 27%. It is generally accepted that the new technologies and more efficient business methods permanently shifted the supply and demand relationship for labor, with labor being in surplus (except during both world wars when the economy was engaged in war-time production and millions of men served in the armed forces). The technologies that became widespread after 1910, such as electrification, internal combustion powered transportation and mass production, were capital saving. Total non-residential fixed business fell after 1910 due to the fall of investment in structures.[248]

Industry, commerce and agriculture[edit]

Two of the most transformative technologies of the century were widely introduced during the early decades: electrification, powered by high pressure boilers and steam turbines and automobiles and trucks powered by the internal combustion engine.[224][249] [250]

Chain stores experienced rapid growth.[232]

Standardization was urged by the Department of Commerce for consumer goods such as bedspreads and screws. A simplified standardization program was issued during World War I.[232]

Electrification[edit]

Electrification was one of the most important drivers of economic growth in the early 20th century. The revolutionary design of electric powered factories caused the period of the highest productivity growth in manufacturing. There was large growth in the electric utility industry and the productivity growth of electric utilities was high as well.[232]

At the turn of the 20th century electricity was used primarily for lighting and most electric companies did not provide daytime service. Electric motors that were used in daytime, such as the DC motors that powered street railways, helped balance the load, and many street railways generated their own electricity and also operated as electric utilities. The AC motor, developed in the 1890s, was ideal for industrial and commercial power and greatly increased the demand for electricity, particular during daytime.[91]

Electrification in the U.S. started in industry around 1900, and by 1930 about 80% of power used in industry was electric. Electric utilities with central generating stations using steam turbines greatly lowered the cost of power, with businesses and houses in cities becoming electrified.[91] In 1900 only 3% of households had electricity, increasing to 30% by 1930. By 1940 almost all urban households had electricity. Electrical appliances such as irons, cooking appliances and washing machines were slowly adopted by households. Household mechanical refrigerators were introduced in 1919 but were in only about 8% of households by 1930, mainly because of their high cost.[224]

The electrical power industry had high productivity growth. Many large central power stations, equipped with high pressure boilers and steam turbine generators began being built after 1913. These central stations were designed for efficient handling of coal from the layout of the rail yards to the conveyor systems. They were also much more fuel efficient, lowering the amount of fuel per kilowatt-hour of electricity to a small fraction of what it had been. In 1900 it took 7 lbs coal to generate one kilowatt hour. In 1960 it took 0.9 lb/kw hr.[251]

Electric street railways[edit]

Electric street railways developed into a major mode of transportation, and electric inter-urban service connected many cities in the Northeast and Midwest. Electric street railways also carried freight, which was important before trucks became widely introduced.[230] The widespread adoption of the automobile and motor bus halted the expansion of the electric street railways during the 1920s.[256]

Electrification

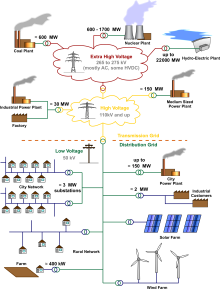

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic history, and economic development, usually applies to a region or national economy. Broadly speaking, electrification was the build-out of the electricity generation and electric power distribution systems that occurred in Britain, the United States, and other now-developed countries from the mid-1880s until around 1950 and is still in progress in rural areas in some developing countries. This included the transition in manufacturing from line shaft and belt drive using steam engines and water power to electric motors.[1][2]

The electrification of particular sectors of the economy is called by terms such as factory electrification, household electrification, rural electrification or railway electrification. It may also apply to changing industrial processes such as smelting, melting, separating or refining from coal or coke heating, or chemical processes to some type of electric process such as electric arc furnace, electric induction or resistance heating, or electrolysis or electrolytic separating.

History of electrification[edit]

The earliest commercial uses of electricity were electroplating and the telegraph.

Development of magnetos, dynamos and generators[edit]

In the years 1831–1832, Michael Faraday discovered the operating principle of electromagnetic generators. The principle, later called Faraday's law, is that an electromotive force is generated in an electrical conductor that is subjected to a varying magnetic flux, as for example, a wire moving through a magnetic field. He also built the first electromagnetic generator, called the Faraday disk, a type of homopolar generator, using a copper disc rotating between the poles of a horseshoe magnet. It produced a small DC voltage.

Around 1832, Hippolyte Pixii improved the magneto by using a wire wound horseshoe, with the extra coils of conductor generating more current, but it was AC. André-Marie Ampère suggested a means of converting current from Pixii's magneto to DC using a rocking switch. Later segmented commutators were used to produce direct current.[4]

William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone developed a telegraph around 1838-40. In 1840 Wheatstone was using a magneto that he developed to power the telegraph. Wheatstone and Cooke made an important improvement in electrical generation by using a battery-powered electromagnet in place of a permanent magnet, which they patented in 1845.[5] The self-excited magnetic field dynamo did away with the battery to power electromagnets. This type of dynamo was made by several people in 1866.

The first practical generator, the Gramme machine, was made by Z. T. Gramme, who sold many of these machines in the 1870s. British engineer R. E. B. Crompton improved the generator to allow better air cooling and made other mechanical improvements. Compound winding, which gave more stable voltage with load, improved the operating characteristics of generators.[6]

The improvements in electrical generation technology in the 19th century increased its efficiency and reliability greatly. The first magnetos only converted a few percent of mechanical energy to electricity. By the end of the 19th century the highest efficiencies were over 90%.

Electric lighting[edit]

Arc lighting[edit]

Sir Humphry Davy invented the carbon arc lamp in 1802 upon discovering that electricity could produce a light arc with carbon electrodes. However, it was not used to any great extent until a practical means of generating electricity was developed.

Carbon arc lamps were started by making contact between two carbon electrodes, which were then separated to within a narrow gap. Because the carbon burned away, the gap had to be constantly readjusted. Several mechanisms were developed to regulate the arc. A common approach was to feed a carbon electrode by gravity and maintain the gap with a pair of electromagnets, one of which retracted the upper carbon after the arc was started and the second controlled a brake on the gravity feed.[7]

Arc lamps of the time had very intense light output – in the range of 4000 candlepower (candelas) – and released a lot of heat, and they were a fire hazard, all of which made them inappropriate for lighting homes.[4]

In the 1850s, many of these problems were solved by the arc lamp invented by William Petrie and William Staite. The lamp used a magneto-electric generator and had a self-regulating mechanism to control the gap between the two carbon rods. Their light was used to light up the National Gallery in London and was a great novelty at the time. These arc lamps and designs similar to it, powered by large magnetos, were first installed on English lighthouses in the mid 1850s, but the power limitations prevented these models from being a proper success.[8]

The first successful arc lamp was developed by Russian engineer Pavel Yablochkov, and used the Gramme generator. Its advantage lay in the fact that it didn't require the use of a mechanical regulator like its predecessors. It was first exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1878 and was heavily promoted by Gramme.[9] The arc light was installed along the half mile length of Avenue de l'Opéra, Place du Theatre Francais and around the Place de l'Opéra in 1878.[10]

British engineer R. E. B. Crompton developed a more sophisticated design in 1878 which gave a much brighter and steadier light than the Yablochkov candle. In 1878, he formed Crompton & Co. and began to manufacture, sell and install the Crompton lamp. His concern was one of the first electrical engineering firms in the world.

Incandescent light bulbs[edit]

Various forms of incandescent light bulbs had numerous inventors; however, the most successful early bulbs were those that used a carbon filament sealed in a high vacuum. These were invented by Joseph Swan in 1878 in Britain and by Thomas Edison in 1879 in the US. Edison’s lamp was more successful than Swan’s because Edison used a thinner filament, giving it higher resistance and thus conducting much less current. Edison began commercial production of carbon filament bulbs in 1880. Swan's light began commercial production in 1881.[11]

Swan's house, in Low Fell, Gateshead, was the world's first to have working light bulbs installed. The Lit & Phil Library in Newcastle, was the first public room lit by electric light,[12][13] and the Savoy Theatre was the first public building in the world lit entirely by electricity.[14]

Electric lighting[edit]

Arc lighting[edit]

Sir Humphry Davy invented the carbon arc lamp in 1802 upon discovering that electricity could produce a light arc with carbon electrodes. However, it was not used to any great extent until a practical means of generating electricity was developed.

Carbon arc lamps were started by making contact between two carbon electrodes, which were then separated to within a narrow gap. Because the carbon burned away, the gap had to be constantly readjusted. Several mechanisms were developed to regulate the arc. A common approach was to feed a carbon electrode by gravity and maintain the gap with a pair of electromagnets, one of which retracted the upper carbon after the arc was started and the second controlled a brake on the gravity feed.[7]

Arc lamps of the time had very intense light output – in the range of 4000 candlepower (candelas) – and released a lot of heat, and they were a fire hazard, all of which made them inappropriate for lighting homes.[4]

In the 1850s, many of these problems were solved by the arc lamp invented by William Petrie and William Staite. The lamp used a magneto-electric generator and had a self-regulating mechanism to control the gap between the two carbon rods. Their light was used to light up the National Gallery in London and was a great novelty at the time. These arc lamps and designs similar to it, powered by large magnetos, were first installed on English lighthouses in the mid 1850s, but the power limitations prevented these models from being a proper success.[8]

The first successful arc lamp was developed by Russian engineer Pavel Yablochkov, and used the Gramme generator. Its advantage lay in the fact that it didn't require the use of a mechanical regulator like its predecessors. It was first exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1878 and was heavily promoted by Gramme.[9] The arc light was installed along the half mile length of Avenue de l'Opéra, Place du Theatre Francais and around the Place de l'Opéra in 1878.[10]

British engineer R. E. B. Crompton developed a more sophisticated design in 1878 which gave a much brighter and steadier light than the Yablochkov candle. In 1878, he formed Crompton & Co. and began to manufacture, sell and install the Crompton lamp. His concern was one of the first electrical engineering firms in the world.

Incandescent light bulbs[edit]

Various forms of incandescent light bulbs had numerous inventors; however, the most successful early bulbs were those that used a carbon filament sealed in a high vacuum. These were invented by Joseph Swan in 1878 in Britain and by Thomas Edison in 1879 in the US. Edison’s lamp was more successful than Swan’s because Edison used a thinner filament, giving it higher resistance and thus conducting much less current. Edison began commercial production of carbon filament bulbs in 1880. Swan's light began commercial production in 1881.[11]

Swan's house, in Low Fell, Gateshead, was the world's first to have working light bulbs installed. The Lit & Phil Library in Newcastle, was the first public room lit by electric light,[12][13] and the Savoy Theatre was the first public building in the world lit entirely by electricity.[14]

Central power stations and isolated systems[edit]

The first central station providing public power is believed to be one at Godalming, Surrey, U.K. autumn 1881. The system was proposed after the town failed to reach an agreement on the rate charged by the gas company, so the town council decided to use electricity. The system lit up arc lamps on the main streets and incandescent lamps on a few side streets with hydroelectric power. By 1882 between 8 and 10 households were connected, with a total of 57 lights. The system was not a commercial success and the town reverted to gas.[15]

The first large scale central distribution supply plant was opened at Holborn Viaduct in London in 1882.[16] Equipped with 1000 incandescent lightbulbs that replaced the older gas lighting, the station lit up Holborn Circus including the offices of the General Post Office and the famous City Temple church. The supply was a direct current at 110 V; due to power loss in the copper wires, this amounted to 100 V for the customer.

Within weeks, a parliamentary committee recommended passage of the landmark 1882 Electric Lighting Act, which allowed the licensing of persons, companies or local authorities to supply electricity for any public or private purposes.

The first large scale central power station in America was Edison's Pearl Street Station in New York, which began operating in September 1882. The station had six 200 horsepower Edison dynamos, each powered by a separate steam engine. It was located in a business and commercial district and supplied 110 volt direct current to 85 customers with 400 lamps. By 1884 Pearl Street was supplying 508 customers with 10,164 lamps.[17]

By the mid-1880s, other electric companies were establishing central power stations and distributing electricity, including Crompton & Co. and the Swan Electric Light Company in the UK, Thomson-Houston Electric Company and Westinghouse in the US and Siemens in Germany. By 1890 there were 1000 central stations in operation.[7] The 1902 census listed 3,620 central stations. By 1925 half of power was provided by central stations.[18]

Load factor & isolated systems[edit]

One of the biggest problems facing the early power companies was the hourly variable demand. When lighting was practically the only use of electricity, demand was high during the first hours before the workday and the evening hours when demand peaked.[19] As a consequence, most early electric companies did not provide daytime service, with two-thirds providing no daytime service in 1897.[20]

The ratio of the average load to the peak load of a central station is called the load factor.[19] For electric companies to increase profitability and lower rates, it was necessary to increase the load factor. The way this was eventually accomplished was through motor load.[19] Motors are used more during daytime and many run continuously. (See: Continuous production.) Electric street railways were ideal for load balancing. Many electric railways generated their own power and also sold power and operated distribution systems.[1]

The load factor adjusted upward by the turn of the 20th century—at Pearl Street the load factor increased from 19.3% in 1884 to 29.4% in 1908. By 1929, the load factor around the world was greater than 50%, mainly due to motor load.[21]

Before widespread power distribution from central stations, many factories, large hotels, apartment and office buildings had their own power generation. Often this was economically attractive because the exhaust steam could be used for building and industrial process heat,[7]</ref> which today is known as cogeneration or combined heat and power (CHP). Most self-generated power became uneconomical as power prices fell. As late as the early 20th century, isolated power systems greatly outnumbered central stations.[7] Cogeneration is still commonly practiced in many industries that use large amounts of both steam and power, such as pulp and paper, chemicals and refining. The continued use of private electric generators is called microgeneration.

Direct current electric motors[edit]

The first commutator DC electric motor capable of turning machinery was invented by the British scientist William Sturgeon in 1832.[22] The crucial advance that this represented over the motor demonstrated by Michael Faraday was the incorporation of a commutator. This allowed Sturgeon's motor to be the first capable of providing continuous rotary motion.[23]

Frank J. Sprague improved on the DC motor in 1884 by solving the problem of maintaining a constant speed with varying load and reducing sparking from the brushes. Sprague sold his motor through Edison Co.[24] It is easy to vary speed with DC motors, which made them suited for a number of applications such as electric street railways, machine tools and certain other industrial applications where speed control was desirable.[7]e electric generators is called microgeneration.

Direct current electric motors[edit]

The first commutator DC electric motor capable of turning machinery was invented by the British scientist William Sturgeon in 1832.[22] The crucial advance that this represented over the motor demonstrated by Michael Faraday was the incorporation of a commutator. This allowed Sturgeon's motor to be the first capable of providing continuous rotary motion.[23]

Frank J. Sprague improved on the DC motor in 1884 by solving the problem of maintaining a constant speed with varying load and reducing sparking from the brushes. Sprague sold his motor through Edison Co.[24] It is easy to vary speed with DC motors, which made them suited for a number of applications such as electric street railways, machine tools and certain other industrial applications where speed control was desirable.[7]

Alternating current[edit]

Although the first power stations supplied direct current, the distribution of alternating current soon became the most favored option. The main advantages of AC were that it could be transformed to high voltage to reduce transmission losses and that AC motors could easily run at constant speeds.

Alternating current technology was rooted in Michael Faraday's 1830–31 discovery that a changing magnetic field can induce an electric current in a circuit.[25]

The first person to conceive of a rotating magnetic field was Walter Baily who gave a workable demonstration of his battery-operated polyphase motor aided by a commutator on June 28, 1879 to the Physical Society of London.[26] Nearly identical to Baily’s apparatus, French electrical engineer Marcel Deprez in 1880 published a paper that identified the rotating magnetic field principle and that of a two-phase AC system of currents to produce it.[27] In 1886, English engineer Elihu Thomson built an AC motor by expanding upon the induction-repulsion principle and his wattmeter.[28]

It was in the 1880s that the technology was commercially developed for large scale electricity generation and transmission. In 1882 the British inventor and electrical engineer Sebastian de Ferranti, working for the company Siemens collaborated with the distinguished physicist Lord Kelvin to pioneer AC power technology including an early transformer.[29]

A power transformer developed by Lucien Gaulard and John Dixon Gibbs was demonstrated in London in 1881, and attracted the interest of Westinghouse. They also exhibited the invention in Turin in 1884, where it was adopted for an electric lighting system. Many of their designs were adapted to the particular laws governing electrical distribution in the UK.[citation needed]

Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti went into this business in 1882 when he set up a shop in London designing various electrical devices. Ferranti believed in the success of alternating current power distribution early on, and was one of the few experts in this system in the UK. With the help of Lord Kelvin, Ferranti pioneered the first AC power generator and transformer in 1882.[30] John Hopkinson, a British physicist, invented the three-wire (three-phase) system for the distribution of electrical power, for which he was granted a patent in 1882.[31]

The Italian inventor Galileo Ferraris invented a polyphase AC induction motor in 1885. The idea was that two out-of-phase, but synchronized, currents might be used to produce two magnetic fields that could be combined to produce a rotating field without any need for switching or for moving parts. Other inventors were the American engineers Charles S. Bradley and Nikola Tesla, and the German technician Friedrich August Haselwander.[32] They were able to overcome the problem of starting up the AC motor by using a rotating magnetic field produced by a poly-phase current.[33] Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky introduced the first three-phase induction motor in 1890, a much more capable design that became the prototype used in Europe and the U.S.[34] By 1895 GE and Westinghouse both had AC motors on the market.[35] With single phase current either a capacitor or coil (creating inductance) can be used on part of the circuit inside the motor to create a rotating magnetic field.[36] Multi-speed AC motors that have separately wired poles have long been available, the most common being two speed. Speed of these motors is changed by switching sets of poles on or off, which was done with a special motor starter for larger motors, or a simple multiple speed switch for fractional horsepower motors.

AC power stations[edit]

The first AC power station was built by the English electrical engineer Sebastian de Ferranti. In 1887 the London Electric Supply Corporation hired Ferranti for the design of their power station at Deptford. He designed the building, the generating plant and the distribution system. It was built at the Stowage, a site to the west of the mouth of Deptford Creek once used by the East India Company. Built on an unprecedented scale and pioneering the use of high voltage (10,000 V) AC current, it generated 800 kilowatts and supplied central London. On its completion in 1891 it was the first truly modern power station, supplying high-voltage AC power that was then "stepped down" with transformers for consumer use on each street. This basic system remains in use today around the world.

In America, George Westinghouse who had become interested in the power transformer developed by Gaulard and Gibbs, began to develop his AC lighting system, using a transmission system with a 20:1 step up voltage with step-down. In 1890 Westinghouse and Stanley built a system to transmit power several miles to a mine in Colorado. A decision was taken to use AC for power transmission from the Niagara Power Project to Buffalo, New York. Proposals submitted by vendors in 1890 included DC and compressed air systems. A combination DC and compressed air system remained under consideration until late in the schedule. Despite the protestations of the Niagara commissioner William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) the decision was taken to build an AC system, which had been proposed by both Westinghouse and General Electric. In October 1893 Westinghouse was awarded the contract to provide the first three 5,000 hp, 250 rpm, 25 Hz, two phase generators.[37] The hydro power plant went online in 1895,[38] and it was the largest one until that date.[39]

By the 1890s, single and poly-phase AC was undergoing rapid introduction.[40] In the U.S. by 1902, 61% of generating capacity was AC, increasing to 95% in 1917.[41] Despite the superiority of alternating current for most applications, a few existing DC systems continued to operate for several decades after AC became the standard for new systems.

Steam turbines[edit]

The efficiency of steam prime movers in converting the heat energy of fuel into mechanical work was a critical factor in the economic operation of steam central generating stations. Early projects used reciprocating steam engines, operating at relatively low speeds. The introduction of the steam turbine fundamentally changed the economics of central station operations. Steam turbines could be made in larger ratings than reciprocating engines, and generally had higher efficiency. The speed of steam turbines did not fluctuate cyclically during each revolution; making parallel operation of AC generators feasible, and improved the stability of rotary converters for production of direct current for traction and industrial uses. Steam turbines ran at higher speed than reciprocating engines, not being limited by the allowable speed of a piston in a cylinder. This made them more compatible with AC generators with only two or four poles; no gearbox or belted speed increaser was needed between the engine and the generator. It was costly and ultimately impossible to provide a belt-drive between a low-speed engine and a high-speed generator in the very large ratings required for central station service.

The modern steam turbine was invented in 1884 by the British Sir Charles Parsons, whose first model was connected to a dynamo that generated 7.5 kW (10 hp) of electricity.[42] The invention of Parson's steam turbine made cheap and plentiful electricity possible. Parsons turbines were widely introduced in English central stations by 1894; the first electric supply company in the world to generate electricity using turbo generators was Parsons' own electricity supply company Newcastle and District Electric Lighting Company, set up in 1894.[43] Within Parson's lifetime, the generating capacity of a unit was scaled up by about 10,000 times.[44]

The first U.S. turbines were two De Leval units at Edison Co. in New York in 1895. The first U.S. Parsons turbine was at Westinghouse Air Brake Co. near Pittsburgh.[45]

Steam turbines also had capital cost and operating advantages over reciprocating engines. The condensate from steam engines was contaminated with oil and could not be reused, while condensate from a turbine is clean and typically reused. Steam turbines were a fraction of the size and weight of comparably rated reciprocating steam engine. Steam turbines can operate for years with almost no wear. Reciprocating steam engines required high maintenance. Steam turbines can be manufactured with capacities far larger than any steam engines ever made, giving important economies of scale.

Steam turbines could be built to operate on higher pressure and temperature steam. A fundamental principle of thermodynamics is that the higher the temperature of the steam entering an engine, the higher the efficiency. The introduction of steam turbines motivated a series of improvements in temperatures and pressures. The resulting increased conversion efficiency lowered electricity prices.[46]

The power density of boilers was increased by using forced combustion air and by using compressed air to feed pulverized coal. Also, coal handling was mechanized and automated.[47]

Electrical grid[edit]

With the realization of long distance power transmission it was possible to interconnect different central stations to balance loads and improve load factors. Interconnection became increasingly desirable as electrification grew rapidly in the early years of the 20th century.

Charles Merz, of the Merz & McLellan consulting partnership, built the Neptune Bank Power Station near Newcastle upon Tyne in 1901,[48] and by 1912 had developed into the largest integrated power system in Europe.[49] In 1905 he tried to influence Parliament to unify the variety of voltages and frequencies in the country's electricity supply industry, but it was not until World War I that Parliament began to take this idea seriously, appointing him head of a Parliamentary Committee to address the problem. In 1916 Merz pointed out that the UK could use its small size to its advantage, by creating a dense distribution grid to feed its industries efficiently. His findings led to the Williamson Report of 1918, which in turn created the Electricity Supply Bill of 1919. The bill was the first step towards an integrated electricity system in the UK.

The more significant Electricity (Supply) Act of 1926, led to the setting up of the National Grid.[50] The Central Electricity Board standardised the nation's electricity supply and established the first synchronised AC grid, running at 132 kilovolts and 50 Hertz. This started operating as a national system, the National Grid, in 1938.

In the United States it became a national objective after the power crisis during the summer of 1918 in the midst of World War I to consolidate supply. In 1934 the Public Utility Holding Company Act recognized electric utilities as public goods of importance along with gas, water, and telephone companies and thereby were given outlined restrictions and regulatory oversight of their operations.[51]

Finance, money and banking[edit]

A major economic downturn in 1906 ended the expansion from the late 1890s. This was followed by the Panic of 1907. The Panic of 1907 was a factor in the establishment of the Federal Reserve Bank in 1913.[262]

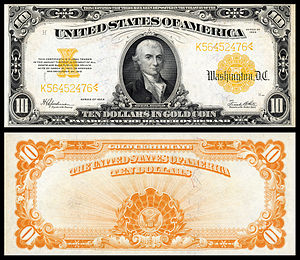

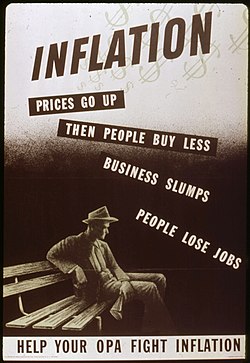

The mild inflation of the 1890s, attributed to the rising gold supply from mining, continued until World War I, at which time inflation rose sharply with wartime shortages including labor shortages. Following the war the rate of inflation fell, but prices remained above the prewar level.[226]

The U.S. economy prospered during World War I, partly due to sales of war goods to Europe. The stock market had its best year in history in 1916. The U.S. gold reserves doubled between 1913 and 1918, causing the price level to rise. Interest rates had been held low to minimize interest on war bonds, but after the final war bonds were sold in 1919, the Federal Reserve raised the discount rate from 4% to 6%. Interest rates rose and the money supply contracted. The economy entered the Depression of 1920-21, which was a sharp decline financially. By 1923, the economy had returned to full employment.[263]

A debt-fueled boom developed following the war. Jerome (1934) gives an unattributed quote about finance conditions that allowed the great industrial expansion of the post World War I period:

There was also a real estate and housing bubble in the 1920s, especially in Florida, which burst in 1925. Alvin Hansen stated that housing construction during the 1920s decade exceeded population growth by 25%.[265] See also:Florida land boom of the 1920s

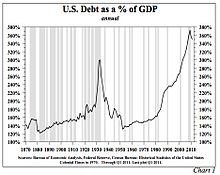

Debt reached unsustainable levels. Speculation in stocks drove prices up to unprecedented valuation levels. The stock market crashed in late October 1929.

Political developments[edit]

The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was the first of a series of legislation that led to the establishment of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Another such act passed the same year was the Federal Meat Inspection Act. The new laws helped the large packers, and hurt small operations that lacked economy of scale or quality controls.[266]

The Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which allowed the Federal Government to tax all income, was adopted in 1913.

The Emergency Quota Act (1921) established a quota system on immigrants by country of origin, with the maximum number of annual immigrants from a country limited to 3% of the number of that national background living in the U.S. according to the 1910 United States Census. The Immigration Act of 1924 reduced the quota from 3% to 2% and added additional restrictions on certain nationalities.

In the early years of American history, most political leaders were reluctant to involve the federal government too heavily in the private sector, except in the area of transportation. In general, they accepted the concept of laissez-faire, a doctrine opposing government interference in the economy except to maintain law and order. This attitude started to change during the latter part of the 19th century, when small business, farm, and labor movements began asking the government to intercede on their behalf.[267]

By the start of the 20th century, a middle class had developed that was leery of both the business elite and the somewhat radical political movements of farmers and laborers in the Midwest and West. Known as Progressives, these people favored government regulation of business practices to, in their minds, ensure competition and free enterprise. Congress enacted a law regulating railroads in 1887 (the Interstate Commerce Act), and one preventing large firms from controlling a single industry in 1890 (the Sherman Antitrust Act). These laws were not rigorously enforced, however, until the years between 1900 and 1920, when Republican President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), Democrat President Woodrow Wilson (1913–1921), and others sympathetic to the views of the Progressives came to power. Many of today's U.S. regulatory agencies were created during these years, including the Interstate Commerce Commission and the Federal Trade Commission. Ida M. Tarbell wrote a series of articles against the Standard Oil monopoly. The series helped pave the way for the breakup of the monopoly.[267]

Muckrakers were journalists who encouraged readers to demand more regulation of business. Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906) showed America the horrors of the Chicago Union Stock Yards, a giant complex of meat processing that developed in the 1870s. The federal government responded to Sinclair's book with the new regulatory Food and Drug Administration.

When Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected president with a Democrat controlled Congress in 1912 he implemented a series of progressive policies. In 1913, the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified, and the income tax was instituted in the United States. Wilson resolved the longstanding debates over tariffs and antitrust, and created the Federal Reserve, a complex business-government partnership that to this day dominates the financial world.

World War I[edit]

The World War involved a massive mobilization of money, taxes, and banking resources to pay for the American war effort and, through government-to-government loans, most of the Allied war effort as well.[268]

Roaring Twenties: 1920–1929[edit]

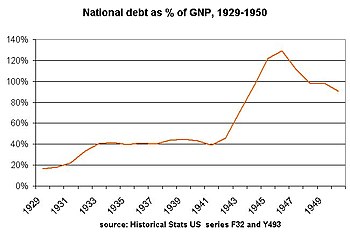

Under Republican President Warren G. Harding, who called for normalcy and an end to high wartime taxes, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon raised the tariff, cut marginal tax rates and used the large surplus to reduce the federal debt by about a third from 1920 to 1930. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover worked to introduce efficiency, by regulating business practices. This period of prosperity, along with the culture of the time, was known as the Roaring Twenties. The rapid growth of the automobile industry stimulated industries such as oil, glass, and road-building. Tourism soared and consumers with cars had a much wider radius for their shopping. Small cities prospered, and large cities had their best decade ever, with a boom in construction of offices, factories and homes. The new electric power industry transformed both business and everyday life. Telephones and electricity spread to the countryside, but farmers never recovered from the wartime bubble in land prices. Millions migrated to nearby cities. However, in October 1929, the Stock market crashed and banks began to fail in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[269]

Quality of life[edit]

The early decades of the 20th century were remarkable for the improvements of the quality of life in the U.S. The quality of housing improved, with houses offering better protection against cold. Floor space per occupant increased. Sanitation was greatly improved by the building of water supply and sewage systems, plus the treatment of drinking water by filtration and chlorination. The change over to internal combustion took horses off the streets and eliminated horse manure and urine and the flies they attracted.[224] Federal regulation of food products and processing, including government inspection of meat processing plants helped lower the incidence of food related illness and death.[224]

Infant mortality, which had been declining dramatically in the last quarter of the 19th century, continued to decline.[224]

The workweek, which averaged 53 hours in 1900, continued to decline. The burden of household chores lessened considerably. Hauling water and firewood into the home every day was no longer necessary for an increasing number of households.[224]

Electric light was far less expensive and higher quality than kerosene lamp light. Electric light also eliminated smoke and fumes and reduced the fire hazard.[230]

Welfare capitalism[edit]

Beginning in the 1880s but especially by the 1920s, some large non-union corporations such as Kodak, Sears, and IBM, adopted the philosophy of paternalistic welfare capitalism. In this system, workers are considered an important stakeholder alongside owners and customers. In return for loyalty to the company, workers get long-term job security, health care, defined benefit pension plans, and other perks. Welfare capitalism was seen as good for society, but also for the economic interests of the company as a way to prevent unionization, government regulation, and socialism or Communism, which became a major concern in the 1910s. By the 1980s, the philosophy had declined in popularity in favor of maximizing shareholder value at the expense of workers, and defined contribution plans such as 401(k)s, replaced guaranteed pensions.Muckrakers were journalists who encouraged readers to demand more regulation of business. Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906) showed America the horrors of the Chicago Union Stock Yards, a giant complex of meat processing that developed in the 1870s. The federal government responded to Sinclair's book with the new regulatory Food and Drug Administration.

When Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected president with a Democrat controlled Congress in 1912 he implemented a series of progressive policies. In 1913, the Sixteenth Amendment was ratified, and the income tax was instituted in the United States. Wilson resolved the longstanding debates over tariffs and antitrust, and created the Federal Reserve, a complex business-government partnership that to this day dominates the financial world.

World War I[edit]

The World War involved a massive mobilization of money, taxes, and banking resources to pay for the American war effort and, through government-to-government loans, most of the Allied war effort as well.[268]

Roaring Twenties: 1920–1929[edit]

Under Republican President Warren G. Harding, who called for normalcy and an end to high wartime taxes, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon raised the tariff, cut marginal tax rates and used the large surplus to reduce the federal debt by about a third from 1920 to 1930. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover worked to introduce efficiency, by regulating business practices. This period of prosperity, along with the culture of the time, was known as the Roaring Twenties. The rapid growth of the automobile industry stimulated industries such as oil, glass, and road-building. Tourism soared and consumers with cars had a much wider radius for their shopping. Small cities prospered, and large cities had their best decade ever, with a boom in construction of offices, factories and homes. The new electric power industry transformed both business and everyday life. Telephones and electricity spread to the countryside, but farmers never recovered from the wartime bubble in land prices. Millions migrated to nearby cities. However, in October 1929, the Stock market crashed and banks began to fail in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[269]

Quality of life[edit]

The early decades of the 20th century were remarkable for the improvements of the quality of life in the U.S. The quality of housing improved, with houses offering better protection against cold. Floor space per occupant increased. Sanitation was greatly improved by the building of water supply and sewage systems, plus the treatment of drinking water by filtration and chlorination. The change over to internal combustion took horses off the streets and eliminated horse manure and urine and the flies they attracted.[224] Federal regulation of food products and processing, including government inspection of meat processing plants helped lower the incidence of food related illness and death.[224]

Infant mortality, which had been declining dramatically in the last quarter of the 19th century, continued to decline.[224]

The workweek, which averaged 53 hours in 1900, continued to decline. The burden of household chores lessened considerably. Hauling water and firewood into the home every day was no longer necessary for an increasing number of households.[224]

Electric light was far less expensive and higher quality than kerosene lamp light. Electric light also eliminated smoke and fumes and reduced the fire hazard.[230]

Causes of the Great Depression

The causes of the Great Depression in the early 20th century in the United States have been extensively discussed by economists and remain a matter of active debate.[1] They are part of the larger debate about economic crises and recessions. The specific economic events that took place during the Great Depression are well established. There was an initial stock market crash that triggered a "panic sell-off" of assets. This was followed by a deflation in asset and commodity prices, dramatic drops in demand and credit, and disruption of trade, ultimately resulting in widespread unemployment (over 13 million people were unemployed by 1932) and impoverishment. However, economists and historians have not reached a consensus on the causal relationships between various events and government economic policies in causing or ameliorating the Depression.

Current mainstream theories may be broadly classified into two main points of view. The first are the demand-driven theories, from Keynesian and institutional economists who argue that the depression was caused by a widespread loss of confidence that led to drastically lower investment and persistent underconsumption. The demand-driven theories argue that the financial crisis following the 1929 crash led to a sudden and persistent reduction in consumption and investment spending, causing the depression that followed.[2] Once panic and deflation set in, many people believed they could avoid further losses by keeping clear of the markets. Holding money therefore became profitable as prices dropped lower and a given amount of money bought ever more goods, exacerbating the drop in demand.

Second, there are the monetarists, who believe that the Great Depression started as an ordinary recession, but that significant policy mistakes by monetary authorities (especially the Federal Reserve) caused a shrinking of the money supply which greatly exacerbated the economic situation, causing a recession to descend into the Great Depression.[3] Related to this explanation are those who point to debt deflation causing those who borrow to owe ever more in real terms.

There are also several various heterodox theories that reject the explanations of the Keynesians and monetarists. Some new classical macroeconomists have argued that various labor market policies imposed at the start caused the length and severity of the Great Depression.

General theoretical reasoning[edit]

The two classical competing theories of the Great Depression are the Keynesian (demand-driven) and the monetarist explanation. There are also various heterodox theories that downplay or reject the explanations of the Keynesians and monetarists.

Economists and economic historians are almost evenly split as to whether the traditional monetary explanation that monetary forces were the primary cause of the Great Depression is right, or the traditional Keynesian explanation that a fall in autonomous spending, particularly investment, is the primary explanation for the onset of the Great Depression.[4] Today the controversy is of lesser importance since there is mainstream support for the debt deflation theory and the expectations hypothesis that building on the monetary explanation of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz add non-monetary explanations.

There is consensus that the Federal Reserve System should have cut short the process of monetary deflation and banking collapse. If the Fed had done that, the economic downturn would have been far less severe and much shorter.[5]