Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laërtius (/daɪˌɒdʒɪniːz leɪˈɜːrʃiəs/ dy-OJ-in-eez lay-UR-shee-əs;[1] Greek: Διογένης Λαέρτιος, Laertios; fl. 3rd century AD) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek philosophy. His reputation is controversial among scholars because he often repeats information from his sources without critically evaluating it. He also frequently focuses on trivial or insignificant details of his subjects' lives while ignoring important details of their philosophical teachings and he sometimes fails to distinguish between earlier and later teachings of specific philosophical schools. However, unlike many other ancient secondary sources, Diogenes Laërtius generally reports philosophical teachings without attempting to reinterpret or expand on them, which means his accounts are often closer to the primary sources. Due to the loss of so many of the primary sources on which Diogenes relied, his work has become the foremost surviving source on the history of Greek philosophy.

Suda

The Suda or Souda (/ˈsuːdə/; Medieval Greek: Σοῦδα, romanized: Soûda; Latin: Suidae Lexicon)[1] is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas (Σουίδας). It is an encyclopedic lexicon, written in Greek, with 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often derived from medieval Christian compilers.

Title[edit]

The derivation is probably[2] from the Byzantine Greek word souda, meaning "fortress" or "stronghold", with the alternate name, Suidas, stemming from an error made by Eustathius, who mistook the title for the author's name.[3]

A more recent theory by Carlo Maria Mazzucchi (Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milan) sees the composition of the encyclopedia as a collective work, probably in a school; during the process, the entries (from more than forty sources) were written down on file cards collected in a fitting receptacle, before having been transcribed on quires. This happened before 970, and then further entries were added in the margins. Mazzucchi explains the name Σοῦδα (meaning "ditch")[4] as both an acrostic of Συναγωγὴ ὁνομάτων ὑπὸ διαφὸρων ἁρμοσθεῖσα ("Collection of nouns assembled from different [sources]") and a memory of the receptacle which used to contain the file cards.[5] Most likely the name is the acronym ΣΟΥΙΔΑ = ΣΥΝΤΑΞΙΣ ΟΝΟΜΑΣΤΙΚΗΣ ΥΛΗΣ ΙΔΙΑ ΑΛΦΑΒΗΤΙΚΗΣ (ΣΕΙΡΑΣ): Composition of Named Subjects in (by) Alphabetical (Order). It is clearly stated upfront: ΤΟ ΜΕΝ ΠΑΡΟΝ ΒΙΒΛΙΟΝ, ΣΟYΙΔΑ. ΟΙ ΔΕ ΣΥΝΤΑΞΑΜΕΝΟΙ ΤΟΥΤΟ ΑΝΔΡΕΣ ΣΟΦΟΙ. (THE PRESENT BOOK, SOYΙDA. THOSE THAT COMPOSED IT WISE MEN). There are eleven wise men listed along with details of their specific contributions.

Content and sources[edit]

The Suda is somewhere between a grammatical dictionary and an encyclopedia in the modern sense. It explains the source, derivation, and meaning of words according to the philology of its period, using such earlier authorities as Harpocration and Helladios.[6][7] It is a rich source of ancient and Byzantine history and life, although not every article is of equal quality, and it is an "uncritical" compilation.[6]

Much of the work is probably interpolated,[6] and passages that refer to Michael Psellos (c. 1017–1078) are deemed interpolations which were added in later copies.[6]

Biographical notices[edit]

This lexicon contains numerous biographical notices on political, ecclesiastical, and literary figures of the Byzantine Empire to the tenth century, those biographical entries being condensations from the works of Hesychius of Miletus, as the author himself avers. Other sources were the encyclopedia of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (reigned 912–959) for the figures in ancient history, excerpts of John of Antioch (seventh century) for Roman history, the chronicle of Hamartolus (Georgios Monachos, 9th century) for the Byzantine age.[7][6][9] The biographies of Diogenes Laërtius, and the works of Athenaeus and Philostratus. Other principal sources include a lexicon by "Eudemus," perhaps derived from the work On Rhetorical Language by Eudemus of Argos.[10]

Lost scholia[edit]

The lexicon copiously draws from scholia to the classics (Homer, Aristophanes, Thucydides, Sophocles, etc.), and for later writers, Polybius, Josephus, the Chronicon Paschale, George Syncellus, George Hamartolus, and so on.[6][7] The Suda quotes or paraphrases these sources at length. Since many of the originals are lost, the Suda serves as an invaluable repository of literary history, and this preservation of the "literary history" is more vital than the lexicographical compilation itself, by some estimation.[7]

Organization[edit]

The lexicon is arranged alphabetically with some slight deviations from common vowel order and place in the Greek alphabet[6] (including at each case the homophonous digraphs, e.g. αι, ει, οι, that had been previously, earlier in the history of Greek, distinct diphthongs or vowels) according to a system (formerly common in many languages) called antistoichia (ἀντιστοιχία); namely the letters follow phonetically in order of sound, in the pronunciation of the tenth century which is similar to that of Modern Greek. The order is:

In addition, double letters are treated as single for the purposes of collation (as gemination had ceased to be distinctive). The system is not difficult to learn and remember, but some editors—for example, Immanuel Bekker – rearranged the Suda alphabetically.

Background[edit]

Little is known about the author, named "Suidas" in its prefatory note.[6] He probably lived in the second half of the 10th century, because the death of emperor John I Tzimiskes and his succession by Basil II and Constantine VIII are mentioned in the entry under "Adam" which is appended with a brief chronology of the world.[6] At any rate, the work must have appeared by the 12th century, since it is frequently quoted from and alluded to by Eustathius who lived from about 1115 AD to about 1195 or 1196.[6] It has also been stated that the work was a collective work, thus not having had a single author, and that the name which it is known under does not refer to a specific person.[12]

The work deals with biblical as well as pagan subjects, from which it is inferred that the writer was a Christian.[6] In any case, it lacks definite guidelines besides some minor interest in religious matters.[12]

The standard printed edition was compiled by Danish classical scholar Ada Adler in the first half of the twentieth century. A modern translation, the Suda On Line, was completed on 21 July 2014.[13]

The Suda has a near-contemporaneous Islamic parallel, the Kitab al-Fehrest of Ibn al-Nadim. Compare also the Latin Speculum Maius, authored in the 13th century by Vincent of Beauvais.

Life[edit]

Laërtius must have lived after Sextus Empiricus (c. 200), whom he mentions, and before Stephanus of Byzantium and Sopater of Apamea (c. 500), who quote him. His work makes no mention of Neoplatonism, even though it is addressed to a woman who was "an enthusiastic Platonist".[2] Hence he is assumed to have flourished in the first half of the 3rd century, during the reign of Alexander Severus (222–235) and his successors.[3]

The precise form of his name is uncertain. The ancient manuscripts invariably refer to a "Laertius Diogenes", and this form of the name is repeated by Sopater[4] and the Suda.[5] The modern form "Diogenes Laertius" is much rarer, used by Stephanus of Byzantium,[6] and in a lemma to the Greek Anthology.[7] He is also referred to as "Laertes"[8] or simply "Diogenes".[9]

The origin of the name "Laertius" is also uncertain. Stephanus of Byzantium refers to him as "Διογένης ὁ Λαερτιεύς" (Diogenes ho Laertieus),[10] implying that he was the native of some town, perhaps the Laerte in Caria (or another Laerte in Cilicia). Another suggestion is that one of his ancestors had for a patron a member of the Roman family of the Laërtii.[11] The prevailing modern theory is that "Laertius" is a nickname (derived from the Homeric epithet Diogenes Laertiade, used in addressing Odysseus) used to distinguish him from the many other people called Diogenes in the ancient world.[12]

His home town is unknown (at best uncertain, even according to a hypothesis that Laertius refers to his origin). A disputed passage in his writings has been used to suggest that it was Nicaea in Bithynia.[13][14]

It has been suggested that Diogenes was an Epicurean or a Pyrrhonist. He passionately defends Epicurus[15] in Book 10, which is of high quality and contains three long letters attributed to Epicurus explaining Epicurean doctrines.[16] He is impartial to all schools, in the manner of the Pyrrhonists, and he carries the succession of Pyrrhonism further than that of the other schools. At one point, he even seems to refer to the Pyrrhonists as "our school."[13] On the other hand, most of these points can be explained by the way he uncritically copies from his sources. It is by no means certain that he adhered to any school, and he is usually more attentive to biographical details.[17]

In addition to the Lives, Diogenes refers to another work that he had written in verse on famous men, in various metres, which he called Epigrammata or Pammetros (Πάμμετρος).[3]

Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers[edit]

The work by which he is known, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers (Greek: Βίοι καὶ γνῶμαι τῶν ἐν φιλοσοφίᾳ εὐδοκιμησάντων; Latin: Vitae Philosophorum), was written in Greek and professes to give an account of the lives and sayings of the Greek philosophers.

Although it is at best an uncritical and unphilosophical compilation, its value, as giving us an insight into the private lives of the Greek sages, led Montaigne to write that he wished that instead of one Laërtius there had been a dozen.[18] On the other hand, modern scholars have advised that we treat Diogenes' testimonia with care, especially when he fails to cite his sources: "Diogenes has acquired an importance out of all proportion to his merits because the loss of many primary sources and of the earlier secondary compilations has accidentally left him the chief continuous source for the history of Greek philosophy".[19]

Diogenes divides his subjects into two "schools" which he describes as the Ionian/Ionic and the Italian/Italic; the division is somewhat dubious and appears to be drawn from the lost doxography of Sotion. The biographies of the "Ionian school" begin with Anaximander and end with Clitomachus, Theophrastus and Chrysippus; the "Italian" begins with Pythagoras and ends with Epicurus. The Socratic school, with its various branches, is classed with the Ionic, while the Eleatics and Pyrrhonists are treated under the Italic.

Organization of the work[edit]

Laërtius treats his subject in two divisions which he describes as the Ionian and the Italian schools. The biographies of the former begin with Anaximander, and end with Clitomachus, Theophrastus and Chrysippus; the latter begins with Pythagoras, and ends with Epicurus. The Socratic school, with its various branches, is classed with the Ionic; while the Eleatics and Pyrrhonists are treated under the Italic. He also includes his own poetic verse, albeit pedestrian, about the philosophers he discusses.

The work contains incidental remarks on many other philosophers, and there are useful accounts concerning Hegesias, Anniceris, and Theodorus (Cyrenaics);[20] Persaeus (Stoic);[21] and Metrodorus and Hermarchus (Epicureans).[22] Book VII is incomplete and breaks off during the life of Chrysippus. From a table of contents in one of the manuscripts (manuscript P), this book is known to have continued with Zeno of Tarsus, Diogenes, Apollodorus, Boethus, Mnesarchus, Mnasagoras, Nestor, Basilides, Dardanus, Antipater, Heraclides, Sosigenes, Panaetius, Hecato, Posidonius, Athenodorus, another Athenodorus, Antipater, Arius, and Cornutus. The whole of Book X is devoted to Epicurus, and contains three long letters written by Epicurus, which explain Epicurean doctrines.

His chief authorities were Favorinus and Diocles of Magnesia, but his work also draws (either directly or indirectly) on books by Antisthenes of Rhodes, Alexander Polyhistor, and Demetrius of Magnesia, as well as works by Hippobotus, Aristippus, Panaetius, Apollodorus of Athens, Sosicrates, Satyrus, Sotion, Neanthes, Hermippus, Antigonus, Heraclides, Hieronymus, and Pamphila.[23][24]

Oldest extant manuscripts[edit]

There are many extant manuscripts of the Lives, although none of them are especially old, and they all descend from a common ancestor, because they all lack the end of Book VII.[25] The three most useful manuscripts are known as B, P, and F. Manuscript B (Codex Borbonicus) dates from the 12th century, and is in the National Library of Naples.[a] Manuscript P (Paris) is dated to the 11th/12th century, and is in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[27] Manuscript F (Florence) is dated to the 13th century, and is in the Laurentian Library.[27] The titles for the individual biographies used in modern editions are absent from these earliest manuscripts, however they can be found inserted into the blank spaces and margins of manuscript P by a later hand.[27]

There seem to have been some early Latin translations, but they no longer survive. A 10th-century work entitled Tractatus de dictis philosophorum shows some knowledge of Diogenes.[28] Henry Aristippus, in the 12th century, is known to have translated at least some of the work into Latin, and in the 14th century an unknown author made use of a Latin translation for his De vita et moribus philosophorum[28] (attributed erroneously to Walter Burley).

Pre-Greek and non-Greek tribes (later Hellenized)[edit]

Pre-Greek and non-Greek tribes who became hellenized and whom some of the later Greek tribes claimed descent from

- Anatolians?

- Cadmeans

- Eteocypriots ("True Cypriots") - They lived scattered through Cyprus island.

- Minoan Cretans (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Eteocretans? ("True Cretans") - They lived in the eastern region of Crete island.

- Bottiaeans? - They originally lived in Bottiaea, after Macedonian conquest many of them migrated to Bottike

- Minyans (Minyes) (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Mysians?

- Pelasgians (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships and in Trojan Battle Order) - They lived scattered through several regions of ancient Greece (like Pelasgiotis) in enclaves.

- Aethices/Aethikes - They lived on Mount Pindus and in the neighborhood of Mount Tomarus.

- Attican Pelasgians - They lived in Attica in scattered communities. Later they were fully assimilated into an Attican Ionian Greek ethnic identity.

- Crestones - They lived in Crestonia (southern slopes of Bertiscus Mount, today's Vertiskos Mount; Vertiskos village is on the slopes), to the north of the Mygdonia, to the northeast of Thessalonika).

- Cretan Pelasgians - They lived in parts of Crete island along with other peoples of the island: Eteocretans ("True Cretans" or Cretans proper), Achaean and Dorian Greeks and the Cydonians (of the city of Cydonia/modern Chania).

- Hellespontus Pelasgians - They lived in the Thracian Chersonesus (today's Gallipoli Peninsula) and some parts on the coast of the other side of the Hellespontus or Dardanelles strait (on the Asian side) before the Thracian expansion and conquest of that peninsula.

- Lemnian Pelasgians - They lived in Lemnos island, in the North Aegean Sea. They were conquered by Athens at the end of the 6th century BC and later assimilated into an Ionian Greek identity. Some of them moved to the peninsula's promontory of Actē (today's Mount Athos).

- Cynurians - They lived in Cynuria (Cynuria had two enclaves, one on the coast of eastern Peloponnese Peninsula, between Laconia and Argolis, and another inland, in the far southwestern Arcadia, also called Parrhasia) but it is not certain if Cynurians of East Peloponnese coast and Cynurians of the inland (Arcadia) were the same people, two branches of an original people or even if they were directly related.

- Arcadian Cynurians/Inland Cynurians (Arcadian Pelasgians/Parrhasia Pelasgians) - They lived in far southwestern Arcadia (an inland region of Peloponnese), that was also called Parrhasia, around Mount Lykaion/Lycaeus.

- East Peloponnese Coastal Cynurians - They lived on the coast of eastern Peloponnese Peninsula, from the coast to the eastern slopes of Mount Parnon.

- Hyantes Pelasgians (legendary or partly based on a true people and historical events) - Former Pelasgians inhabitants of Boeotia, from which country they were expelled by the followers of Cadmus (Peck; Pliny's Natural History, iv.12).

- Pelasgiotes - They lived in Pelasgiotis (eastern Thessaly that included Thessaly's own capital Larissa).

- Propontis Pelasgians - They lived in some islands (Marmara, Aphousia) and parts of the southern coast of the Propontis (today's Marmara Sea), mostly in Cyzicus.

- Samothracian Pelasgians - They lived in the island of Samothrace in the North Aegean Sea, south of Thrace. They were conquered by Athens at the beginning of the 5th century BC and later assimilated into an Ionian Greek identity.

- Phrygians?

- Thracians?

- Pieres - They originally lived in Pieria, after Macedonian conquest many of them migrated to Pieris

Western Greek tribes (Dorians and Macedonians)- Dorians - They spoke Doric Greek dialects (that were not descendants of Mycenean Greek but from a common Proto-Greek language).

- Northwestern Doric Greek tribes - They spoke North-West Doric Greek dialect

- Acarnanians, Northwestern Greek - They lived in Acarnania (this region had two groups of Greeks: the native Northwestern Greek Acarnanians and the Dorians Proper Acarnanians, many of whom were descendants from Corinthian colonies).

- Achaean Dorians - Many were Achaeans assimilated by Dorians. They spoke a Northwest Greek dialect but with a stronger Achaean Greek substrate. They spoke Achaean Doric Greek (not to be confused with Achaean Greek).

- Achaean Dorians of Peloponnese - They lived in Achaea (whose older name was Aegialus/Aegialea and was dwelt by Ionians) (North Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Achaean Dorians Diaspora

- Crotoneans - They lived in Crotone (Eastern Calabria coast), Magna Graecia (many were descendants from an Achaean colony from the city of Rhypes).

- Achaean Dorians Diaspora

- Achaean Dorians of the Islands

- Doulicheis - Older dwellers of Leucas/Lefkada Island (before Corinthian colonization). Before Dorian Invasion or migration it was dwelt by Ionians (thus the name Ionic Islands).

- Ithacians - They lived in Ithaca Island (the land of the legendary Odysseus, the main character of the Odyssey and also one of the main ones in the Iliad whose author is traditionally thought to be Homer). Before Dorian Invasion or migration it was dwelt by Ionians (thus the name Ionic Islands).

- Kefalloneis - They lived in Kephalonia Island. Before Dorian Invasion or migration it was dwelt by Ionians (thus the name Ionic Islands).

- Zakynthians - They lived in Zakynthos Island. Before Dorian Invasion or migration it was dwelt by Ionians (thus the name Ionic Islands).

- Achaean Dorians of Peloponnese - They lived in Achaea (whose older name was Aegialus/Aegialea and was dwelt by Ionians) (North Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Aenianians - They lived in Aeniania/Ainis.

- Aetolians/Curetes - They lived in Aetolia.

- Amphilochians - They lived in Amphilochia.

- Eleans - They lived in Elis (West Peloponnese Peninsula). Olympia, where the Ancient Olympic Games were held, was in Elis.

- Epirotes (Epirotic Dorians) - They lived in Epirus.

- Atintanes[5]

- Chaonians - They lived in Chaonia.

- Subtribes or Clans: Dassaretae

- Molossians - A tribal confederation. They lived in Molossis/Molossia.

- Amantes/Abantes/Avantes[6] (?) - They lived in Amantia.(there is ongoing debate on if the tribe was Epirote Greek or Illyrian.)

- Apheidantes - They were named after king Apheidas.

- Arktanoi[7]

- Athamanians (or Athamanes) - They lived in Athamania

- Dodonaioi or Selloi[8] - Dodona sanctuary and oracle was in their land.

- Lyncestai[9] They lived in Lynkestis.

- Orestaes - They lived in Orestis.

- Parauaei/Paroraioi - They lived in Parauaea, Northern Pindus Mountains.

- Paroraioi (Paroraei) - They lived in the western slopes of Mount Tymphe, Northern Pindus Mountains.

- Pelagones[9] - They lived in Pelagonia.

- Talares - They lived on Mount Pindus and in the neighborhood of Mount Tomarus.

- Tymphaeans - They lived in Tymphaea, eastern slopes of Mount Tymphe.

- Thesprotians - They lived in Thesprotia.

- Subtribes or Clans: Aegestaeoi; Chimerioi; Eleaeoi; Elinoi; Ephyroi; Elopes; Fanoteis; Farganaeoi; Fylates; Graeci; Ikadotoi; Kartatoi; Kassopaioi (Kassopaeans);[10] Kestrinoi; Klauthrioi; Kropioi; Larissaeoi; Onopernoi; Opatoi; Parauaioi; Tiaeoi; Torydaeoi.

- Locrians - They lived in Locris.

- Malians - They lived in Malia/Malis. Thermopylae was in their land.

- Oeteans - They lived in Oetaea, included Mount Oeta.

- Phoceans - They lived in Phocis. Delphi sanctuary and oracle was in their land (on the southern slopes of Mount Parnassus).

- Dorians Proper They spoke Doric Greek dialects.

- Oldest tribes (Phylai)

- Argives - They lived in Argolis (East Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Corinthians - They lived in Corinthia (Isthmus of Corinth and North-East Peloponnese Peninsula). Many Greek colonies were of Corinthian origin (i.e. Corinth was the Metropolis - Mother City, the origin of many Greek colonies).

- Corinthian Diaspora

- Acarnanians, Dorians Proper - They lived in Acarnania (this region had two groups of Greeks: the native Northwestern Greek Acarnanians and the Dorians Proper Acarnanians, many of whom were descendants from Corinthian colonies).

- Ambracians - Descendants of a Corinthian colony. They lived in Ambracia.

- Kerkyreans/Corcyraeans - Descendants of a Corinthian colony. They lived in Kerkyra/Corfu (Corcyra). (Phaeacians may have been the original inhabitants and called their island Scheria).

- Leucadians - Descendants of a Corinthian colony. They lived in Leucas (Lefkada) Island.

- Syracusans - They lived in Syracuse in South-East Sicily Island, Magna Graecia (many were descendants from a Corinthian colony).

- Corinthian Diaspora

- Cretans - They lived in Crete Island.

- Cythereans - They lived in Cythera (Kythera/Kythira) Island, south of Peloponnese Peninsula.

- Dorians (of Doris) - They lived in Doris (Upper Cephissus river valley). They were viewed as a people close to the land were Dorians originated - roughly south Epirus and Aetolia in Northwest Greece (when they migrated towards south).

- Laconians - They lived in Laconia (South Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Spartans-Lacedaemonians - They lived in Sparta/Lacedaemon a part of Laconia (South Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Spartan Diaspora

- Tarantinoi - They lived in Taranto, Magna Graecia (many were descendants from a Spartan colony).

- Spartan Diaspora

- Spartans-Lacedaemonians - They lived in Sparta/Lacedaemon a part of Laconia (South Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Megareans - They lived in Megaris.

- Messenians - They lived in Messenia (South-West Peloponnese Peninsula).

- Thereans - They lived in Thera/Thira Island (Santorini).

- Dorian Diaspora

- Northwestern Doric Greek tribes - They spoke North-West Doric Greek dialect

- Dorians - They spoke Doric Greek dialects (that were not descendants of Mycenean Greek but from a common Proto-Greek language).

- Macedonians-Magnetes

- Macedonians (Makedónes) - They lived in Ancient Macedonia and may have spoken a version of the Doric dialect.

- Magnetes - They lived in Magnesia (most of Thessaly's coastal region). They were seen by ancient Greeks as a people that shared a common ancestor with the Macedonians.

- Tyrrhenians?

Iron Age: Archaic and Classical Greece (from circa 800 BC)[edit]

Archaic and Classical Greece after Late Bronze Age collapse and Dorian Invasion

Hellenes[edit]

- Central and Eastern Greek tribes (Aeolians, Achaeans and Ionians)

- Achaeans (Broader sense) - They lived in Eastern, East Central and Southern Greece (Mycenean Greece) before Dorian migrations or Dorian invasions (after that most Achaeans were displaced or assimilated by Dorians in Southern Greece regions, except for Arcadia). They spoke Mycenean Greek that was the ancestor of Aeolic, Arcado-Cypriot and Ionic Greek dialects of Classical Greece.

- Central Greek tribes (Aeolians and Achaeans)

- Aeolians - They spoke Aeolic Greek dialects (archaic dialects that preserved some Mycenean Greek features).

- Boeotians - They lived in Boeotia (Aonia)

- Dryopes - They lived in Dryopis, later known as Doris (after driven out by the Malians, a Dorian tribe, many scattered to other Greek regions, mostly towards far southern of Euboea Island).

- Thessalians - They lived in Thessaly (Thessalia/Aeolia). Mount Olympus is on the border between Thessaly and Macedon.

- Achaeans, Phtiothis - They lived in Achaea Phthiotis.

- Dolopes? - They lived in Dolopia (mostly considered a Thessalian tribe)

- Histiaeoteans - They lived in Histiaeotis, Thessaly's Northwest district.

- Thessalians Proper - They lived in Thessaliotis.

- Aeolian Diaspora

- Asia Minor Aeolians - They lived in Aeolis, Northwestern Anatolian coast.

- Lesbians - They lived in Lesbos Island.

- Achaeans (Narrower sense) (Arcado-Cyprian tribes) - They spoke Arcado-Cypriot Greek dialects (archaic dialects that preserved some Mycenean Greek features).

- Arcadians - They lived in Arcadia (Central Peloponnese Peninsula) and were a pre-Dorian invasion or Dorian migration Greek tribal confederation.

- Azanes

- Triphylians - They were a group of three tribes (Tri - Three, Phylai -Tribes) that lived in Western Peloponnese, in southern part of Elis (south of Alpheiós river) but saw themselves as Arcadians and not Eleans.

- Achaean Diaspora

- Cypriots - They lived in Cyprus Island

- Pamphylians - They lived in Pamphylia (South-West Anatolia).

- Arcadians - They lived in Arcadia (Central Peloponnese Peninsula) and were a pre-Dorian invasion or Dorian migration Greek tribal confederation.

- Aeolians - They spoke Aeolic Greek dialects (archaic dialects that preserved some Mycenean Greek features).

- Eastern Greek tribes (Ionians)

- Ionians - They spoke Ionic Greek dialects (basis of the Greek Koiné and his descendant Modern Greek).

- Oldest tribes (Phylai)

- Attics - They lived in Attica (included ancient Athenians) (Marathon is in Attica)

- Aiantis (named after Ajax) (Aeschylus was a member of this tribe)

- Aigeis (named after Aegeus)

- Akamantis/Acamantis (named after Acamas) (Pericles was a member of this tribe)

- Antiochis (named after Antiochus, son of Heracles) (Socrates was a member of this tribe)

- Erechtheis (named after Erechtheus) (Critias may also have been a member of this tribe)

- Hippothontis (named after Hippothoon)

- Kekropis (named after Cécrops)

- Leontis (named after Leos, son of Orpheus) (Themistocles was a member of this tribe)

- Oineis (named after Oeneus)

- Pandionis (named after Pandion)

- Euboeans (West Ionians) - They lived in Euboea Island.

- Abantes

- Euboean Diaspora

- Chalcidicians, Euboean - They lived in the Peninsula of Chalcidicia (many were descendants from Euboean colonies from the cities of Chalcis and Eretria).

- Catanians - They lived in Catania, Magna Graecia (many were descendants from a Euboean colony from the city of Chalcis).

- Cumaeans - They lived in Cumae, that was founded by settlers from Euboea island (from Chalcis and Eretria cities) in Magna Graecia. It was one of the Greek colonies that most influenced ancient Etruscan and Roman cultures, namely by the introduction of the Alphabet. Cumae by itself was the Metropolis of other poleis in southern Italy coast, including Nea Polis (New City), today's Naples (it was to the West and close of Naples).

- Neapolitans - They lived in Naples (many were descendants from Rhodean and Ionic colonies, the last ones were more numerous).

- Ionians, Cycladian (Central Ionians) - They lived in Cyclades Islands. Delos Island that had the important Delos sanctuary was in this group of islands.

- Cycladian Diaspora

- Chalcidicians, Cycladian - They lived in the Peninsula of Chalcidicia (many were descendants of a colony from Andros Island).

- Cycladian Diaspora

- Salamineans - in Salamis/Salamina Island

- Ionian Diaspora

- Asia Minor Ionians (East Ionians) - They lived in Ionia, Western Anatolian coast.

- Sirisians - They lived in Siris in Lucania/Basilicata eastern coast (many were descendants of a colony from the city of Colophon, in the Western Anatolian coast).

List of ancient Greek tribes

Part of a series on Indo-European topics

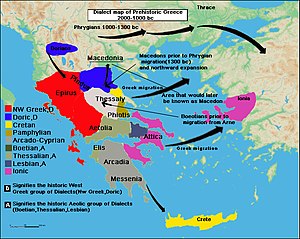

The ancient Greek tribes (Ancient Greek: Ἑλλήνων ἔθνη) were groups of Greek-speaking populations living in Greece, Cyprus, and the various Greek colonies. They were primarily divided by geographic, dialectal, political, and cultural criteria, as well as distinct traditions in mythology and religion. Some groups were of mixed origin, forming a syncretic culture through absorption and assimilation of previous and neighboring populations into the Greek language and customs. Greek word for tribe was Phylē (sing.) and Phylai (pl.), the tribe was further subdivided in Demes (sing. Demos, pl. Demoi) roughly matching to a clan.

With the dominion of land passing on from one tribe to the other, cultural exchange through art and trade, and frequent alliances toward common goals, the ethnic character of the different tribes had become primarily political by the dawn of the Hellenistic period. The Roman conquest of Greece, the subsequent division of the Roman Empire into Greek East and Latin West, as well as the advent of Christianity, molded the common ethnic and political Greek identity once and for all to the subjects of the Greek world by the 3rd century AD.

Ancestors[edit]

- Proto-Indo-Europeans (Proto-Indo-European speakers

- (?) Proto-Graeco-Phrygians (proposed subgroup of Proto-Graeco-Phrygian speakers)[1]

- (?) Proto-Graeco-Armenians (proposed subgroup of Proto-Graeco-Armenian speakers)[2]

- (?) Proto-Graeco-Aryans (proposed subgroup of Proto-Graeco-Aryan speakers)[3]

- Proto-Greeks (Proto-Greek speakers)

Greek tribes[edit]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018)Late Bronze Age: Homeric Age of the Iliad (circa 1200 BC)[edit]

Hellenes[edit]

- Achaeans/Argives/Danaans (Danaoi)/Hellenes/Panhellenes (used as synonym of Greeks by Homer in the Iliad) (Mycenaean Greece before Late Bronze Age collapse and Dorian Invasion)

- Central and Eastern Greek tribes (Aeolians, Achaeans and Ionians)

- Achaeans (Broader sense)

- Central Greek tribes (Aeolians and Achaeans)

- Aeolians

- Acarnanians, Pre-Dorian Acarnanians

- Dulichiumians/Doulicheis (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Taphians and Teleboans - in the Echinades Islands

- Cephallenians - Original dwellers of Cephalonia/Kefalonia, Ithaca (homeland of Odysseus), Leucas/Lefkada and Zakynthos (Southern Ionian Islands) (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Aenianes/Enienes - Pre-Dorian Aenianes of Aenis

- Boeotians

- Aones (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Curetes or Aetolians (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Dryopes - Pre-Dorian dwellers of Doris

- Locrians - Pre-Dorian Locrians (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Phoceans - Pre-Dorian Phoceans (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Thessalians

- Lapiths (Lapíthai) (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships) (Phlegyas was their mythical king)

- Myrmidons (Myrmidónes) (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships) (people of Achilles in the Iliad)

- Perrhaebi (Perraiboí) (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Acarnanians, Pre-Dorian Acarnanians

- Achaeans (Narrower sense) - Pre-Doric people of Peloponnese Peninsula (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Arcadians (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Argives - Pre-Doric people of Argos (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Epeans (el) of Elis (Epeioí) - Pre-Doric people of Elis (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Lacedaemonians - Pre-Doric people of Lacedaemonia, later doric Sparta (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Mycenaeans - Pre-Doric Myceneans, Mycenae was their main settlement (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Symians (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Aeolians

- Eastern Greek tribes (Ionians)

- Ionians

- Oldest tribes (Phylai)

- Attics

- Athenians (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Euboeans

- Salamineans (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Ionians

- Central Greek tribes (Aeolians and Achaeans)

- Achaeans (Broader sense)

- Western Greek tribes (Dorians and Magnetes)

- Dorians

- Oldest tribes (Phylai)

- Northwestern Doric Greek tribes

- Magnetes (mentioned in Iliad's Catalogue of Ships)

- Dorians

- Central and Eastern Greek tribes (Aeolians, Achaeans and Ionians)

- Proto-Indo-Europeans (Proto-Indo-European speakers

- Sirisians - They lived in Siris in Lucania/Basilicata eastern coast (many were descendants of a colony from the city of Colophon, in the Western Anatolian coast).

- Asia Minor Ionians (East Ionians) - They lived in Ionia, Western Anatolian coast.

- Ionians - They spoke Ionic Greek dialects (basis of the Greek Koiné and his descendant Modern Greek).

- Central Greek tribes (Aeolians and Achaeans)

- Achaeans (Broader sense) - They lived in Eastern, East Central and Southern Greece (Mycenean Greece) before Dorian migrations or Dorian invasions (after that most Achaeans were displaced or assimilated by Dorians in Southern Greece regions, except for Arcadia). They spoke Mycenean Greek that was the ancestor of Aeolic, Arcado-Cypriot and Ionic Greek dialects of Classical Greece.

- Central and Eastern Greek tribes (Aeolians, Achaeans and Ionians)

Comments

Post a Comment