Ampullae of Lorenzini Electroreception

Ampullae of Lorenzini

Ampullae of Lorenzini (singular Ampulla) are electroreceptors, sense organs able to detect electric fields. They form a network of mucus-filled pores in the skin of cartilaginous fish (sharks, rays, and chimaeras), and of basal actinopterygians (bony fishes) such as reedfish,[1] sturgeon,[2] and lungfish.[1] They are associated with and evolved from the mechanosensory lateral line organs of early vertebrates. Most bony fishes and terrestrial vertebrates have lost their ampullae of Lorenzini.

History[edit]

Ampullae were initially described by Marcello Malpighi and later given an exact description by the Italian physician and ichthyologist Stefano Lorenzini in 1679, though their function was unknown.[3] Electrophysiological experiments in the 20th century suggested a sensibility to temperature, mechanical pressure, and possibly salinity. In 1960 the ampullae were identified as specialized receptor organs for sensing electric fields.[4][5] One of the first descriptions of calcium-activated potassium channels was based on studies of the ampulla of Lorenzini in the skate.[6]

Evolution[edit]

Ampullae of Lorenzini are physically associated with and evolved from the mechanosensory lateral line organs of early vertebrates. Passive electroreception using ampullae is an ancestral trait in the vertebrates, meaning that it was present in their last common ancestor.[7] Ampullae of Lorenzini are present in cartilaginous fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras), lungfishes, bichirs, coelacanths, sturgeons, paddlefishes, aquatic salamanders, and caecilians. Ampullae of Lorenzini appear to have been lost early in the evolution of bony fishes and tetrapods, though the evidence for absence in many groups is incomplete and unsatisfactory.[7]

| Vertebrates |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Anatomy[edit]

Each ampulla is a bundle of sensory cells containing multiple nerve fibres in a sensory bulb (the endampulle) in a collagen sheath, and a gel-filled canal (the ampullengang) which opens to the surface by a pore in the skin. The gel is a glycoprotein-based substance with the same resistivity as seawater, and electrical properties similar to a semiconductor.[8][3][9]

Pores are concentrated in the skin around the snout and mouth of sharks and rays, as well as the anterior nasal flap, barbel, circumnarial fold and lower labial furrow.[10] Canal size typically corresponds to the body size of the animal but the number of ampullae remains the same. The canals of the ampullae of Lorenzini can be pored or non-pored. Non-pored canals do not interact with external fluid movement but serve a function as a tactile receptor to prevent interferences with foreign particles.[10]

Electroreception[edit]

The ampullae detect electric fields in the water, or more precisely the potential difference between the voltage at the skin pore and the voltage at the base of the electroreceptor cells.[11][12][6]

A positive pore stimulus decreases the rate of nerve activity coming from the electroreceptor cells, while a negative pore stimulus increases the rate. Each ampulla contains a single layer of receptor cells, separated by supporting cells. The cells are connected by apical tight junctions so that no current leaks between them. The apical faces of the receptor cells have a small surface area with a high concentration of voltage-dependent calcium channels (which trigger depolarisation) and calcium-activated potassium channels (for repolarisation afterwards).[13]

Because the canal wall has a very high resistance, all the voltage difference between the pore of the canal and the ampulla is dropped across the 50 micron-thick receptor epithelium. Because the basal membranes of the receptor cells have a lower resistance, most of the voltage is dropped across the excitable apical faces which are poised at the threshold. Inward calcium current across the receptor cells depolarises the basal faces, causing a large action potential, a wave of depolarisation followed by repolarisation (as in a nerve fibre). This triggers presynaptic calcium release and release of excitatory transmitter onto the afferent nerve fibres. These fibres signal the size of the detected electric field to the fish's brain.[14]

The ampulla contains large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (BK channels). Sharks are much more sensitive to electric fields than electroreceptive freshwater fish, and indeed than any other animal, with a threshold of sensitivity as low as 5 nV/cm. The collagen jelly, a hydrogel, that fills the ampullae canals has one of the highest proton conductivity capabilities of any material created by organisms. It contains keratan sulfate in 97% water, and has a conductivity of about 1.8 mS/cm.[14][11] All living creatures produce an electrical field caused by muscle contractions; electroreceptive fish may pick up weak electrical stimuli from the muscle contractions of their prey.[6]

The sawfish has more ampullary pores than any other cartilaginous fish, and is considered an electroreception specialist. Sawfish have ampullae of Lorenzini on their head, ventral and dorsal side of their rostrum leading to their gills, and on the dorsal side of their body.[15]

Magnetoreception[edit]

Ampullae of Lorenzini also contribute to the ability to receive geomagnetic information. As magnetic and electrical fields are related, magnetoreception via electromagnetic induction in the ampullae of Lorenzini is possible. Many cartilaginous fish respond to artificially generated magnetic fields in association with food rewards, demonstrating their capability. Magnetoreception may explain the ability of sharks and rays to form strict migratory patterns and to identify their geographic location.[16]

Temperature sense[edit]

The mucus-like substance inside the tubes may perhaps transduce temperature changes into an electrical signal that the animal may use to detect temperature gradients.[17]

Electric ray

(Redirected from Torpedo fish)Electric rays Temporal range:

Marbled electric ray

(Torpedo marmorata)

Lesser electric ray

(Narcine bancroftii)Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes Superorder: Batoidea Order: Torpediniformes

F. de Buen, 1926Families The electric rays are a group of rays, flattened cartilaginous fish with enlarged pectoral fins, composing the order Torpediniformes /tɔːrˈpɛdɪnɪfɔːrmiːz/. They are known for being capable of producing an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending on species, used to stun prey and for defense.[2] There are 69 species in four families.

Perhaps the best known members are those of the genus Torpedo. The torpedo undersea weapon is named after it. The name comes from the Latin torpere, 'to be stiffened or paralyzed', from the effect on someone who touches the fish.[3]

Description[edit]

Electric rays have a rounded pectoral disc with two moderately large rounded-angular (not pointed or hooked) dorsal fins (reduced in some Narcinidae), and a stout muscular tail with a well-developed caudal fin. The body is thick and flabby, with soft loose skin with no dermal denticles or thorns. A pair of kidney-shaped electric organs are at the base of the pectoral fins. The snout is broad, large in the Narcinidae, but reduced in all other families. The mouth, nostrils, and five pairs of gill slits are underneath the disc.[2][4]

Electric rays are found from shallow coastal waters down to at least 1,000 m (3,300 ft) deep. They are sluggish and slow-moving, propelling themselves with their tails, not by using their pectoral fins as other rays do. They feed on invertebrates and small fish. They lie in wait for prey below the sand or other substrate, using their electricity to stun and capture it.[5]

Relationship to humans[edit]

History of research[edit]

The electrogenic properties of electric rays have been known since antiquity, although their nature was not understood. The ancient Greeks used electric rays to numb the pain of childbirth and operations.[2] In his dialogue Meno, Plato has the character Meno accuse Socrates of "stunning" people with his puzzling questions, in a manner similar to the way the torpedo fish stuns with electricity.[6] Scribonius Largus, a Roman physician, recorded the use of torpedo fish for treatment of headaches and gout in his Compositiones Medicae of 46 AD.[7]

In the 1770s the electric organs of the torpedo ray were the subject of Royal Society papers by John Walsh,[8] and John Hunter.[9][10] These appear to have influenced the thinking of Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta – the founders of electrophysiology and electrochemistry.[11][12] Henry Cavendish proposed that electric rays use electricity; he built an artificial ray consisting of fish shaped Leyden jars to successfully mimic their behaviour in 1773.[13]

In folklore[edit]

The torpedo fish, or electric ray, appears continuously in premodern natural histories as a magical creature, and its ability to numb fishermen without seeming to touch them was a significant source of evidence for the belief in occult qualities in nature during the ages before the discovery of electricity as an explanatory mode.[14]

Bioelectricity[edit]

The electric rays have specialised electric organs. Many species of rays and skates outside the family have electric organs in the tail; however, the electric ray has two large kidney-shaped electric organs on each side of its head, where current passes from the lower to the upper surface of the body. The nerves that signal the organ to discharge branch repeatedly, then attach to the lower side of each plaque in the batteries.[2] These are composed of hexagonal columns, closely packed in a honeycomb formation. Each column consists of 500 to more than 1000 plaques of modified striated muscle, adapted from the branchial (gill arch) muscles.[2][15][16] In marine fish, these batteries are connected as a parallel circuit, whereas freshwater batteries are arranged in series. This allows freshwater rays to transmit discharges of higher voltage, as freshwater cannot conduct electricity as well as saltwater.[17] With such a battery, an electric ray may electrocute larger prey with a voltage of between 8 volts in some narcinids to 220 volts in Torpedo nobiliana, the Atlantic torpedo.[2][18]

Systematics[edit]

The 60 or so species of electric rays are grouped into 12 genera and two families.[19] The Narkinae are sometimes elevated to a family, the Narkidae. The torpedinids feed on large prey, which are stunned using their electric organs and swallowed whole, while the narcinids specialize on small prey on or in the bottom substrate. Both groups use electricity for defense, but it is unclear whether the narcinids use electricity in feeding.[20]

- Family Narcinidae (numbfishes)

- Subfamily Narcininae

- Genus Benthobatis

- Genus Diplobatis

- Genus Discopyge

- Genus Narcine

- Subfamily Narkinae (sleeper rays)

- Genus Crassinarke

- Genus Electrolux

- Genus Heteronarce

- Genus Narke

- Genus Temera

- Genus Typhlonarke

- Subfamily Narcininae

- Family Hypnidae (coffin rays)

- Family Torpedinidae (torpedo electric rays)

- Subfamily Torpedininae

- Genus Tetronarce

- Genus Torpedo

Electric fish

An electric fish is any fish that can generate electric fields. Most electric fish are also electroreceptive, meaning that they can sense electric fields. The only exceptions are the stargazers. Electric fish include both oceanic and freshwater species. Many cartilaginous fish such as sharks, rays and catfishes are electroreceptive but not electrogenic.

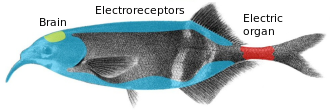

Electric fish produce their electrical fields from an electric organ. This is made up of electrocytes, modified muscle or nerve cells, specialized for producing strong electric fields, used to locate prey, for defence against predators, and for signalling, such as in courtship. Electric organ discharges are two types, pulse and wave, and vary both by species and by function.

Electric fish have evolved many specialised behaviours. The predatory African sharptooth catfish eavesdrops on its weakly electric mormyrid prey to locate it when hunting, driving the prey fish to develop electric signals that are harder to detect. Bluntnose knifefishes produce an electric discharge pattern similar to the electrolocation pattern of the dangerous electric eel, probably a form of Batesian mimicry to dissuade predators. Glass knifefish that are using similar frequencies move their frequencies up or down in a jamming avoidance response; African knifefish have convergently evolved a nearly identical mechanism.

Evolution and phylogeny[edit]

All fish, indeed all vertebrates, use electrical signals in their nerves and muscles.[1] Cartilaginous fishes and some other basal groups use passive electrolocation with sensors that detect electric fields;[2] the platypus and echidna have separately evolved this ability. The knifefishes and elephantfishes actively electrolocate, generating weak electric fields to find prey. Finally, fish in several groups have the ability to deliver electric shocks powerful enough to stun their prey or repel predators. Among these, only the stargazers, a group of marine bony fish, do not also use electrolocation.[3][4]

In vertebrates, electroreception is an ancestral trait, meaning that it was present in their last common ancestor.[2] This form of ancestral electroreception is called ampullary electroreception, from the name of the receptive organs involved, ampullae of Lorenzini. These evolved from the mechanical sensors of the lateral line, and exist in cartilaginous fishes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras), lungfishes, bichirs, coelacanths, sturgeons, paddlefish, aquatic salamanders, and caecilians. Ampullae of Lorenzini were lost early in the evolution of bony fishes and tetrapods. Where electroreception does occur in these groups, it has secondarily been acquired in evolution, using organs other than and not homologous with ampullae of Lorenzini.[2][5] Most common bony fish are non-electric. There are some 350 species of electric fish.[6]

Electric organs have evolved eight times, four of these being organs powerful enough to deliver an electric shock. Each such group is a clade.[7][2] Most electric organs evolved from myogenic tissue (which forms muscle), however one group of gymnotiformes, the Apteronotidae, derived their electric organ from neurogenic tissue (which forms nerves).[8] In Gymnarchus niloticus (the African knifefish), the tail, trunk, hypobranchial, and eye muscles are incorporated into the organ, most likely to provide rigid fixation for the electrodes while swimming. In some other species, the tail fin is lost or reduced. This may reduce lateral bending while swimming, allowing the electric field to remain stable for electrolocation. There has been convergent evolution in these features among the mormyrids and gymnotids. Electric fish species that live in habitats with few obstructions, such as some bottom-living fish, display these features less prominently. This implies that convergence for electrolocation is indeed what has driven the evolution of the electric organs in the two groups.[9]

Actively electrolocating fish are marked on the phylogenetic tree with a small yellow lightning flash

. Fish able to deliver electric shocks are marked with a red lightning flash

. Fish able to deliver electric shocks are marked with a red lightning flash  . Non-electric and purely passively-electrolocating species are not shown.[2][10]

. Non-electric and purely passively-electrolocating species are not shown.[2][10]Vertebrates Chondrichthyes Torpediniformes (electric rays) (69 spp)

Rajiformes (skates) (~200 spp)

430 mya Bony fishes Osteogloss. Mormyridae elephantfishes (~200 spp)

knollenorgans

(pulses)Gymnarchidae African knifefish (1 sp)

knollenorgans

(waves)Gymnotiformes S. Amer. knifefishes Electric eel ampullary

receptorsSiluriformes Electric catfish Uranoscopidae Stargazers (50 spp)

no electro‑

location425 mya Amp. of Lorenzini Weakly electric fish[edit]

Weakly electric fish generate a discharge that is typically less than one volt. These are too weak to stun prey and instead are used for navigation, electrolocation in conjunction with electroreceptors in their skin, and electrocommunication with other electric fish. The major groups of weakly electric fish are the Osteoglossiformes, which include the Mormyridae (elephantfishes) and the African knifefish Gymnarchus, and the Gymnotiformes (South American knifefishes). These two groups have evolved convergently, with similar behaviour and abilities but different types of electroreceptors and differently-sited electric organs.[2][10]

Strongly electric fish[edit]

Strongly electric fish, namely the electric eel, the electric catfishes, the electric rays, and the stargazers, have an electric organ discharge powerful enough to stun prey or be used for defence,[13] and navigation.[14][9][15] The electric eel, even when very small in size, can deliver substantial electric power, and enough current to exceed many species' pain threshold.[16] Electric eels sometimes leap out of the water to electrify possible predators directly, as has been tested with a human arm.[16]

The amplitude of the electrical output from these fish can range from 10 to 860 volts with a current of up to 1 ampere, according to the surroundings, for example different conductances of salt and freshwater. To maximize the power delivered to the surroundings, the impedances of the electric organ and the water must be matched:[12]

- Strongly electric marine fish give low voltage, high current electric discharges. In salt water, a small voltage can drive a large current limited by the internal resistance of the electric organ. Hence, the electric organ consists of many electrocytes in parallel.

- Freshwater fish have high voltage, low current discharges. In freshwater, the power is limited by the voltage needed to drive the current through the large resistance of the medium. Hence, these fish have numerous cells in series.[12]

Electric organ[edit]

Anatomy[edit]

Electric organs vary widely among electric fish groups. They evolved from excitable, electrically-active tissues that make use of action potentials for their function: most derive from muscle tissue, but in some groups the organ derives from nerve tissue.[17] The organ may lie along the body's axis, as in the electric eel and Gymnarchus; it may be in the tail, as in the elephantfishes; or it may be in the head, as in the electric rays and the stargazers.[3][8][18]

Physiology[edit]

Electric organs are made up of electrocytes, large, flat cells that create and store electrical energy, awaiting discharge. The anterior ends of these cells react to stimuli from the nervous system and contain sodium channels. The posterior ends contain sodium–potassium pumps. Electrocytes become polar when triggered by a signal from the nervous system. Neurons release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine; this triggers acetylcholine receptors to open and sodium ions to flow into the electrocytes.[14] The influx of positively charged sodium ions causes the cell membrane to depolarize slightly. This in turn causes the gated sodium channels at the anterior end of the cell to open, and a flood of sodium ions enters the cell. Consequently, the anterior end of the electrocyte becomes highly positive, while the posterior end, which continues to pump out sodium ions, remains negative. This sets up a potential difference (a voltage) between the ends of the cell. After the voltage is released, the cell membranes go back to their resting potentials until they are triggered again.[14]

Discharge patterns[edit]

Electric organ discharges (EODs) need to vary with time for electrolocation, whether with pulses, as in the Mormyridae, or with waves, as in the Torpediniformes and Gymnarchus, the African knifefish.[18][19][20] Many electric fishes also use EODs for communication, while strongly electric species use them for hunting or defence.[19] Their electric signals are often simple and stereotyped, the same on every occasion.[18]

Electrolocation and discharge patterns of electric fishes[20] Group Habitat Electro-

locationDischarge Type Waveform Spike/wave

durationVoltage Torpediniformes

Electric raysSea Active Weak, Strong Wave

10 ms 25 V Rajiformes

SkatesSea Active Weak Pulse

200 ms 0.5 V Mormyridae

ElephantfishesFW Active Weak Pulse

1 ms 0.5 V Gymnarchus

African knifefishFW Active Weak Wave

3 ms < 5 V Gymnotus

Banded knifefishFW Active Weak Pulse

2 ms < 5 V Eigenmannia

Glass knifefishFW Active Weak Wave

5 ms 100 mV Electrophorus

Electric eelsFW Active Strong Pulse

2 ms 600 V[14] Siluriformes

Electric catfishFW Active Strong Pulse

2 ms 25 V Uranoscopidae

StargazersSea None Strong Pulse

10 ms 5 V Electrocommunication[edit]

Weakly electric fish can communicate by modulating the electrical waveform they generate. They may use this to attract mates and in territorial displays.[21]

Sexual behaviour[edit]

In sexually dimorphic signalling, as in the brown ghost knifefish (Apteronotus leptorhynchus), the electric organ produces distinct signals to be received by individuals of the same or other species.[22] The electric organ fires to produce an EOD with a certain frequency, along with short modulations termed "chirps" and "gradual frequency rises", both varying widely between species and differing between the sexes.[23][19] For example, in the glass knifefish genus Eigenmannia, females produce a nearly pure sine wave with few harmonics, males produce a far sharper non-sinusoidal waveform with strong harmonics.[24]

Male bluntnose knifefishes (Brachyhypopomus) produce a continuous electric "hum" to attract females; this consumes 11–22% of their total energy budget, whereas female electrocommunication consumes only 3%. Large males produced signals of larger amplitude, and these are preferred by the females. The cost to males is reduced by a circadian rhythm, with more activity coinciding with night-time courtship and spawning, and less at other times.[25]

Antipredator behaviour[edit]

Electric catfish (Malapteruridae) frequently use their electric discharges to ward off other species from their shelter sites, whereas with their own species they have ritualized fights with open-mouth displays and sometimes bites, but rarely use electric organ discharges.[26]

The electric discharge pattern of bluntnose knifefishes is similar to the low voltage electrolocative discharge of the electric eel. This is thought to be a form of bluffing Batesian mimicry of the powerfully-protected electric eel.[27]

Fish that prey on electrolocating fish may "eavesdrop"[28] on the discharges of their prey to detect them. The electroreceptive African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) may hunt the weakly electric mormyrid, Marcusenius macrolepidotus in this way.[29] This has driven the prey, in an evolutionary arms race, to develop more complex or higher frequency signals that are harder to detect.[30]

Jamming avoidance response[edit]

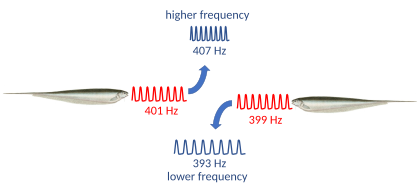

It had been theorized as early as the 1950s that electric fish near each other might experience some type of interference. In 1963, Akira Watanabe and Kimihisa Takeda discovered the jamming avoidance response in Eigenmannia.[31] When two fish are approaching one another, their electric fields interfere.[32] This sets up a beat with a frequency equal to the difference between the discharge frequencies of the two fish.[32] The jamming avoidance response comes into play when fish are exposed to a slow beat. If the neighbour's frequency is higher, the fish lowers its frequency, and vice versa.[31][24] A similar jamming avoidance response was discovered in the distantly-related Gymnarchus niloticus, the African knifefish, by Walter Heiligenberg in 1975, in a further example of convergent evolution between the electric fishes of Africa and South America.[33] Both the neural computational mechanisms and the behavioural responses are nearly identical in the two groups.[34]

See also[edit]

- Family Narcinidae (numbfishes)